South Africans are close to the point where any further increases will result in more tax evasion or a total refusal to pay tax.

No amount of tax planning can reduce the burden of indirect taxes. Picture: Dean Hutton/Bloomberg

Nobody likes to see a few thousand rand in tax disappearing straight off their salary month after month. The tax deduction might equal the instalment on a car for most people, or at least a few extra pizzas every month.

More alarming is that everybody pays thousands more in tax than our salary slips show. The range of indirect taxes – value added tax (Vat), fuel levies and other duties – increase the tax rate on an average salary from an effective rate of around 14% to nearly 30%, depending on what one considers to be an average salary in a very diverse labour market. Salaries differ significantly in different towns, and even due to personal characteristics.

Surveys by employment consultants, Stats SA and the Department of Labour give a wide range of average salaries in different industries – from an average of R6 000 a month for an office assistant to R30 000 for a computer programmer.

Stats SA’s quarterly employment survey puts the average salary in SA during the last quarter of 2018 at R21 190 per month.

This tallies with what one would consider an average job in SA. Advertisements in newspapers and on the internet indicate that a qualified nurse, electrician or accountant with a bit of experience can expect to earn R230 000 to R260 000 per annum. According to one employment agency’s website, the South African Revenue Service (Sars) itself would pay its accountants and tax consultants between R22 000 and R24 000 per month.

Illustrating the impact

A salary of around R23 000 per month will suffice to illustrate the effect of the impact of indirect taxes. The same argument will hold true for somebody who earns R4 000 per month and pays no income tax, but will pay tax of 15% on most of their income in the form of Vat every time they open their wallet in a supermarket.

According to Sars’s tax deduction tables, an individual who earns R276 000 per annum (R23 000 per month) should pay R56 313 tax per year (nearly R4 700 per month), equal to a tax rate of a shade over 20%. In reality, it is less.

The primary rebate will decrease the tax rate to around 14% for individuals below the age of 65, and a measure of tax allowances with regards to retirement annuities and medical expenses will help decrease it further, to around 11%. Good tax planning and a structured remuneration package could decrease the tax rate even more, but probably at the cost of lower cash earnings.

But no amount of tax planning can reduce the burden of indirect taxes. Everybody is aware of the increase in Vat from 14% to 15%, announced in the 2018 budget speech, but the effect of high levies on fuel and life’s sinful pleasures is even worse in terms of the rate of tax.

How it all adds up

If our average salary earner owns a car and drives the average 30 000 kilometres per annum (based on Sars’s assumption of private use of a vehicle and guidelines in the second-hand car market), they will use about 3 000 litres of fuel per annum at some 10 litres per 100 kilometres. At R5.56 in tax per litre, they will pay a massive R16 890 in fuel tax every year.

The balance of our average taxpayer’s salary can result in another R25 000 finding its way to Sars in the form of Vat, depending on how much an individual spends and saves and the products they buy.

A daily packet of (legal) cigarettes will contribute another R15.52 (R5 640 per annum) to government’s treasure chest and a few glasses of beer, wine or brandy can easily add another R3 000 per annum. Spirits are taxed at nearly R46 per bottle, while the sugar tax adds R2.80 to a two-litre bottle of Coke.

Adding a few hundred for property tax, but disregarding capital gains tax and refusing to pay e-tolls, will result in a total tax bill of around R84 000 per annum (R7 000 per month). This means anybody with an average job and average salary pays up to 30% of their income towards tax.

The argument holds true for people earning more as well. Firstly, SA’s progressive tax system taxes higher earners at a higher rate, while people with more money will spend more and drive more. They are also likely to pay more in property tax as well as a bit of capital gains tax from time to time.

Not much bang for our tax buck

However, it is not only the amount of tax or the effective tax rate when including indirect taxes that is making taxpayers unhappy, but rather the impression that we are not getting value for our money.

Government services, for the most part, do not come close to meeting expectations. Just about every government department admits that its service delivery is not up to standard, be it state hospitals, public transport, government schools, safety and security or maintenance of roads. In most municipalities finances and service delivery are in disarray, while Eskom struggles to deliver uninterrupted electricity.

The inefficiency of government is akin to an additional tax as taxpayers need to supplement government services – whether in the form of a back-up generator, expensive medical cover, the services of a private security company, private schools or extra English lessons. This ‘inefficiency tax’ can even extend higher, to life and short-term insurance premiums due to government’s failure to uphold law and order to an acceptable standard.

Tax compliance

The level of tax and what taxpayers get in return in terms of services, as well as the quality of these services, are important aspects that make people question our tax regime and raise concerns about tax compliance.

Johan Rossouw, economist at Vunani Securities, says most taxpayers probably think they are paying too much tax, especially in light of what we really receive for our tax money. “We probably don’t compare well with the rest of the world when comparing our tax rate with what we receive in services.”

Comparing tax rates between countries is complex due to huge differences in tax brackets and significant differences between statutory tax rates and effective tax rates. It is easy to refer to tax rates in extreme cases, such as Sweden, Denmark and Finland, which have maximum marginal income tax rates of around 55% and sales tax as high as 25%. But citizens receive good schooling and healthcare, without direct payment (although there are concerns about whether their government spending is sustainable).

Oil-rich countries in the Middle East are at the other end of the scale, with excellent services at a tax rate of less than 2% and seemingly no constraints on state budgets.

Tipping point

In SA, taxpayers are increasingly of the view that we already pay too much tax and are close to the point where any further increases will result in more tax evasion or a total refusal to pay tax, in a similar vein to the e-tolls boycott.

“I don’t believe we are at this point yet, but we are probably high on the curve,” says Rossouw, referring to the so-called Laffer Curve, which shows how government revenue increases as tax rates increase, but only up to a certain point. Thereafter tax revenue decreases since there is little incentive for people to work harder if government takes most of the extra income, as well as an increase in tax evasion.

“A big concern in SA is the belief that our taxes are not going towards what they are meant for,” says Rossouw. “The general view is that too much disappears due to corruption, theft and inefficiency.”

Hugo Pienaar, economist at the Bureau for Economic Research at the University of Stellenbosch, says the tipping point of tax collection is not a specific figure or an absolute percentage. “Some people might already be inclined to try and evade tax. It is one of the tax authorities’ current challenges – to restore taxpayer confidence.

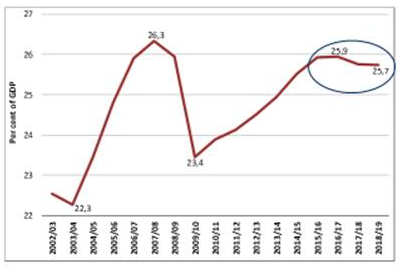

“It is interesting to note that government’s tax income as percentage of the size of the economy declined during the last few years, despite the introduction of new taxes to the tune of R92 billion since 2016,” says Pienaar. “The decrease in tax revenue versus the GDP could be the result of lower economic growth or inefficiency in tax collections, which might include a proportion of tax fatigue.”

Tax revenue as a percentage of GDP

Rossouw and Pienaar both mention that government’s ability to ensure law and order, policy certainty, acceptable service delivery and proper strategic planning with regards to economic and business issues are necessary to rebuild a good relationship with taxpayers to ensure that people feel the heavy tax burden is fair and reasonable.

Brought to you by Moneyweb.

Download our app