There is a lack of understanding of the obstacles that an incoherent government policy creates.

Uncertainty and concerns about the soon-to-be released Mining Charter remain a major hurdle in the South African investment road, says Norton Rose Fulbright’s Kevin Cron, head of corporate mergers and acquisitions.

The charter is expected to be released within weeks, but industry players are “nervous” that the new minister of mineral resources, Gwede Mantashe, may retain controversial provisions that caused so much concern in his predecessor’s charter.

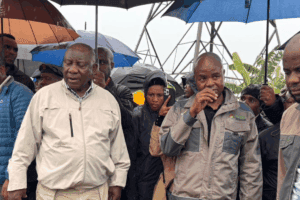

One might end up back in a court battle if this is the case, says Cron. He commented on the policy problems facing the country in achieving the ambitious target of $100 billion in new investments over the next five years announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa.

“It’s all well to say that the country needs foreign investment, and that it has to be an investment destination – [but] government has got to do more than just talk about it.”

He adds that the mining sector, oil and gas in particular, holds significant investment potential, but the legislation and policy issues must be clarified: “Nobody is willing to invest, or to commit significant funds when they do not know what the rules of the game are.”

Ramaphosa said in April that total fixed investment in the economy has declined from 24% of Gross Domestic Product in 2008 to around 19% last year. This has to increase to at least 30% in the next 12 years.

Cron acknowledges that the Zuma legacy has left the new government with an incoherent policy that is preventing investors from opening their hearts and purses to deliver on the hope of a “new dawn”. While there have been welcoming changes in the management of state-owned enterprises, there is a dire need for a coherent policy that is understood and implemented by all state entities.

Ramaphosa has since appointed four special envoys on investment: former minister of finance Trevor Manuel, former deputy minister of finance Mcebisi Jonas, Afropulse executive chairperson Phumzile Langeni, and Liberty Group chairman Jacko Maree.

Cron says it is critical for government to sift through current legislation and find what it is that investors find concerning. It must then decide whether it is absolutely necessary to keep that legislation. He notes that

Ramaphosa has referred to the country’s “thriving democracy, independent judiciary and strong institutions”.

Cron is not convinced that there is a full understanding of the obstacles created by an incoherent government policy. “Frankly, I still think there is a suspicion in government of business in general. When business raises issues of concern, it is often, although not all the time viewed, with suspicion.”

When looking at issues separately, they might not seem that important, but it is when they are put together that a picture of a jurisdiction that is not particularly investor friendly emerges, even though it is not altogether unfriendly.

There are abundant investment opportunities globally, and especially in Africa, and Cron says South Africa should be going out if its way to make itself more attractive to investors – locally and globally. “I am not sure if that is fully appreciated.”

Areas of concern, besides the mining charter, include: the expropriation-without-compensation policy; immigration legislation, which makes it almost impossible to hire foreign professional workers; black economic empowerment requirements for foreign companies; and exchange control issues.

The introduction of a ‘headquarters regime’ to encourage foreign multinational companies to drive the management of their African operations from a base in South Africa remains a fundamentally good idea. However, strict anti-avoidance rules have left it almost dead in the water. Mauritius has really positioned itself as the “jurisdiction of choice” for establishing headquarters for foreign companies’ African operations.

Cron adds that our corporate tax rate remains high when compared to global standards, and on top of that there is no real tax relief for foreign companies in South Africa.

The Davis Tax Committee found in its final report on corporate income tax that the current rate of 28% is on par with the African average of 28.21%. However, it is way above that of the European average of 19.71%, Asia’s 21.28%, the European Union’s 21.51%, and the global average of 24.29%.

The committee recommended no change to the current rate. It felt that other policy measures, together with political and social uncertainty, would still act as disincentives for further or new investments. These policy measures include immigration laws, the ability to guarantee electricity and water supplies, security of tenure and corruption.

Brought to you by Moneyweb

For more news your way, follow The Citizen on Facebook and Twitter.