Leicester relegated from the Premier League as Liverpool close in on title

Adept at navigating Yemen’s complex politics, he survived civil war, rebellion in the north, an Al-Qaeda insurgency in the south and a June 2011 bomb attack on his palace that wounded him badly.

In 2014 he allied with his former enemies, Huthi Shiite rebels from Yemen’s north, to seek revenge against those who forced him from power.

But the collapse of their alliance was the beginning of the end for the wily leader.

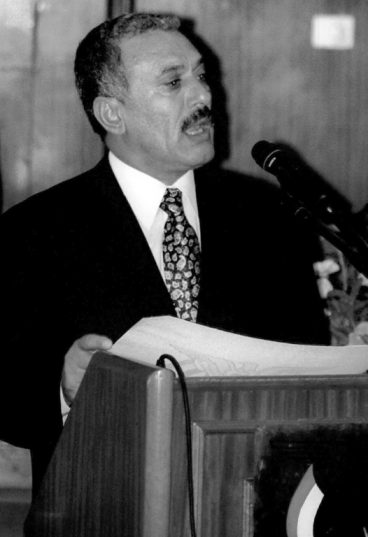

A stocky man with piercing eyes and a moustache, Saleh was for decades Yemen’s most powerful man.

In 2015, a UN panel of experts accused him of corruption, saying he may have amassed up to $60 billion the country descended into poverty during his 33 years in power.

A picture from June 1, 2000 shows Ali Abdullah Saleh diving during free time at his private presidential club

Hailing from the same Zaidi minority as the Huthis, Saleh joined the army aged 20 and took part in the 1962 coup against Yemen’s Zaidi imamate.

The ensuing six-year civil war ended in victory for Egyptian-backed nationalists who in 1968 formed the Yemen Arab Republic, also known as North Yemen.

A few months earlier, an independent South Yemen had been formed following the British withdrawal. It would eventually become the Communist-ruled People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen.

– Reunification –

Saleh showed his leadership skills at an early age and swiftly climbed North Yemen’s military and political ladder.

Following the June 1978 assassination of president Ahmad al-Ghashmi, a constituent assembly elected Saleh — by then a colonel — president of North Yemen.

He immediately surrounded himself with close aides, notably his brothers, appointing them to key military and security posts.

Saleh deftly steered the country towards reunification in 1990 and four years later crushed a southern secession bid.

Ali Abdullah Saleh addressing parliament in Sanaa in October 2001

He became Yemen’s first directly elected president in 1999, winning more than 96 percent of the vote, but elections during his tenure were widely criticised and he was accused of stifling dissent.

Saleh became a US ally in the fight against Al-Qaeda, allowing drone strikes on Yemeni territory, the first of which in 2002 killed the group’s Yemen chief, Qaed Salim Sinan al-Harithi.

Between 2004 and 2010, Saleh fought several wars against the Huthis, who had long complained of marginalisation.

In the late 2000s he also grappled with growing pro-independence demonstrations in the south.

But the first real challenge to his rule came with the eruption in 2011 of Arab Spring-inspired protests that brought thousands of people onto the streets.

Saleh clung to power amid a deadly crackdown on demonstrators demanding an end to his regime.

He left Yemen for Saudi Arabia in June 2011 to receive medical treatment after being burned in a bomb attack on his presidential compound, but returned less than four months later.

He eventually ceded power in February 2012 under a Gulf-brokered deal that granted him immunity from prosecution.

– ‘Dancing on snakes’ –

Vice President Abedrabbo Mansour Hadi took power after Saleh’s resignation but struggled to assert his authority.

The ex-president remained behind the scenes, refusing to go into exile and remaining head of his General People’s Congress party.

The Huthis’ seizure of Sanaa in September 2014 would have been impossible without support from Saleh loyalists, analysts said.

An expert report to the UN Security Council alleged Saleh provided “direct support” to the Huthis through funding and the backing of elite forces still under his influence.

Hadi in February 2015 fled to the southern city of Aden after escaping house arrest in Sanaa, then to Saudi Arabia as the rebels advanced south.

Yassin Makkawi, an adviser to Hadi, in 2015 described the ex-president as a “tyrant”, saying “the Huthis are puppets in the hands of Saleh”.

A coalition led by Saudi Arabia, which feared the Huthis would help its arch-rival Iran spread its influence in Yemen, launched air strikes and sent ground troops to Yemen in support of Hadi.

That escalation has since killed more than 8,750 people and dragged Yemen towards what the UN calls the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The intervention helped loyalists win back control of large parts of the south but they were unable to dislodge the Huthis from Sanaa and other key strongholds.

Saleh was reported to have remained in the capital and boasted: “I will never leave Sanaa.”

But in mid-2017, his alliance with the Huthis began to collapse amid simmering resentment over money, power-sharing and suspected backdoor dealings.

When Saleh reached out to the Saudi-led coalition last week, the Huthis accused him of “great treason” and staging a “coup” against “an alliance he never believed in”.

A smart tactician who had portrayed himself as a “saviour” after his resignation, Saleh once compared ruling Yemen to “dancing on the heads of snakes”.

But Saleh’s gamble in quitting his alliance with the Huthis proved to be a fatal step.

As gun battles rocked the capital on Monday, the Huthis announced that Saleh had been killed, and a video supplied to AFP by the rebels showed what appeared to be his corpse.

Hours later, his party confirmed the news.

At the age of 75, the man who had shaped much of Yemen’s post-independence history was dead.

Download our app