Polish mountaineer Tomasz Mackiewicz, whom France's Elisabeth Revol was forced to leave behind weak and bleeding on a Himalayan peak nicknamed "killer mountain" to save her own life, made a name for himself as a free spirit.

“We’ve lost one of the most free and independent men out there,” Polish mountaineer Wojciech Kurtyka said.

Revol was facing death on Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat when Polish elite climbers Adam Bielecki and Denis Urubko scaled part of the 8,125-metre (26,660-foot) mountain in darkness last month to rescue her.

But they were unable to save Mackiewicz.

“Were we to have left Eli and gone looking for Tomek, she would have died. We couldn’t leave her, she wouldn’t have survived the night,” Urubko told Polish daily Gazeta Wyborcza.

Polish climbing legend Leszek Cichy described Mackiewicz, 43, to AFP as “a character, different from others, very fascinating”.

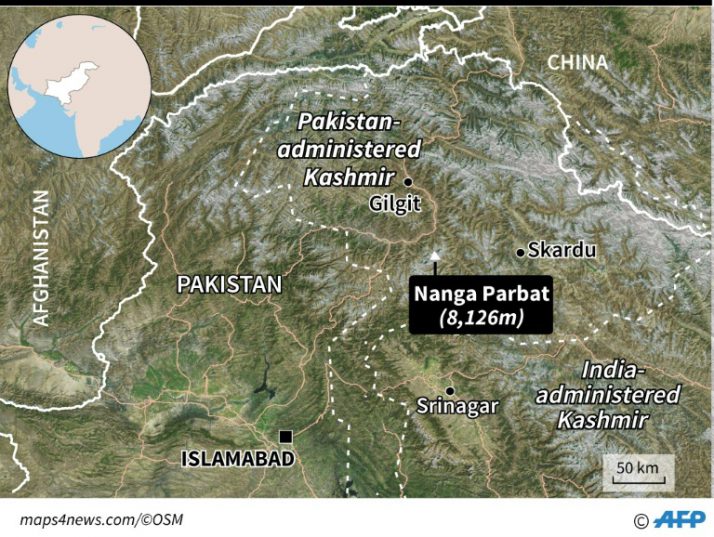

Map of Pakistan locating Nanga Parbat

“Kind, warm, open, he was a man from another planet for whom material goods didn’t matter and who wanted to experience mountains in the humblest way possible,” said Cichy, known for achieving the world’s first summit of Everest in winter with fellow countryman Krzysztof Wielicki.

Long before he devoted himself to the Himalayas, Mackiewicz battled a heroin addiction in the 1990s that he kicked after two years in rehab.

He then bought a small yacht and sailed around the Masurian lakes in northern Poland, before hitchhiking to India to teach English to children afflicted with leprosy for six months.

– At home in the Himalayas –

Though he did some hiking and spelunking when he was younger, it was only in Asia that he first saw the massive mountains that he would later go on to climb.

Members of the Polish K2 expedition rescued French climber Elisabeth Revol in Nanga Parbat on January 28, 2018

An elite group of climbers saved a French mountaineer in a daring high-altitude rescue mission on Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat, one of the highest mountains in the world, as officials called off the search for a second missing alpinist on January 28.

Next, he travelled around Ireland, then returned to Poland and notably earned a living by installing wind turbines.

His first major mountaineering expedition took him and fellow free spirit Marek Klonowski to Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak at 5,959 metres.

The six-week journey, during which they braved temperatures that sometimes dropped to minus 40 degrees Celsius, earned them a Polish travel award in 2008.

Mackiewicz then summited Khan Tengri (7,010 metres) in Kazakhstan on his own, before reuniting with Klonowski to take a stab at Nanga Parbat.

The idea was to climb the mountain in winter, which no one had yet done before, and to “show that anyone could dream, that the Himalayas were accessible to anyone,” Klonowski said.

Mackiewicz would end up heading to Nanga Parbat a total of seven times. He always brought along bags of stuff for the locals.

“He’d show up at the villages at the foot of Nanga and everyone knew him. He felt at home there,” said Cichy.

– Outsider –

During one of their early expeditions, Mackiewicz and Klonowski set off with ropes meant for agricultural use that they had bought online for a discount.

They had so little money on them that they were forced to sell all their equipment and clothes to pay for their flight home, returning to wintertime Warsaw in T-shirts.

They had neither official support nor recognition from Poland’s climbing elite, which considered them outsiders for a long time.

Though they returned with their heads down, they did not give up. On yet another attempt they managed to reach the 7,200-metre mark.

Later he began climbing with Revol. On their second expedition together — and Mackiewicz’s sixth — the conditions were so extreme that they experienced real fear and had to turn back.

“‘Eli, it’s impossible,'” Mackiewicz later recalled saying.

“For the first time I saw her afraid. And when you’re afraid, you lose your motivation,” he told reporters in 2016.

“You have the option of continuing and seeing how it goes. But that’s insanity because you don’t want to die. What will happen to your kids? I’m happy to have turned back. Life is beautiful,” said the twice-married father-of-three.

He returned one last time with Revol to finally conquer the mountain — and he stayed.

“He really wanted to summit that mountain, and he did,” Revol told AFP.