In a constantly changing country where all eyes are fixed on the future, Nigerian artist Johnson Uwadinma is fixated by the past.

“If you do not know where you are coming from, how then do you know where you are going to?” he asks.

For his project, “Amnesia”, he has stuck together hundreds of balls made from old crumpled up newspaper and painted in bright colours, like a mass of strange molecules.

The piece — symbolising the many unresolved crises Nigeria has faced over decades — was on show last weekend at the contemporary art fair, “Art X Lagos”.

“The media constantly repeats the same stories about corruption, war, violence, deceit,” said Uwadinma. “We never learn from our past.”

– ‘Programmed forgetfulness’ –

Uwadinma hails from the southeast, where 50 years ago, the military governor in charge of the region, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, declared an independent republic of Biafra for the Igbo majority there.

That triggered a bloody civil war that lasted 30 months and left more than one million dead.

But Uwadinma, 35, said: “This story, like the atrocities committed by successive military regimes, is not taught at school.”

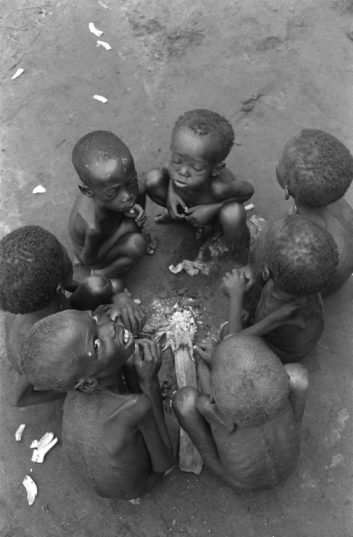

The world was stunned by pictures of starving children in the Biafran war. But the atrocities have been wiped from Nigeria’s collective memory, says Uwadinma

Ten years ago, the federal government even withdrew history from primary and secondary school teaching, deeming it not to be an essential subject for students as future jobseekers.

There have been mounting calls in politics and academia for it to be reintroduced.

For Uwadinma, “the way we recycle the news is a symptom of the way we trash our memory and look for the next trendy story”.

This “programmed forgetfulness” has not stopped the West African oil giant, with its population hurtling towards 200 million, from developing at a pace since the return of civilian rule at the end of the 1990s.

Nigeria — a driver of the whole continent — is a source of fascination with its economic dynamism, flourishing cinema industry Nollywood and billionaire pop stars.

But the glitzy icons are a far cry from the music legend of the 1970s and 80s, Fela Kuti and his anti-establishment Afrobeat.

“We only hear about money, girls and parties, it’s out of touch with reality,” said Uwadinma.

– Pop-up gallery –

The second edition of Art X this year saw works shown from more than 60 artists from 15 African countries at 14 galleries.

Celine Seror, the co-founder of the pan-African Intense Art Magazine (IAM), described it as a crossroads of “very intense, very rich” cultural exchange.

“It connects Nigerian artists and the whole continent with politicians and rich major collectors who could buy their art,” she said.

“They’re exploring ‘classic’ themes of contemporary art such as the body, intimacy… but there are also a lot of works with a strong political message about corruption or even the wealth gap.”

For Zina Saro-Wiwa, even if the event has a clear commercial side, art must before anything else “mobilise the spirit, create value”.

A curator, artist and film-maker, Saro-Wiwa is also the daughter of the Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was executed in 1995 by Sani Abacha’s military regime.

Her father led a popular movement that brought global attention to the devastating pollution by foreign oil companies, including Shell, in his native Ogoniland.

Three years ago, Zina Saro-Wiwa decided to return to her roots in the Niger Delta to “explore the legacy” of her father.

She created “Boys’ Quarters” in her father’s old office in a working class area of the oil hub Port Harcourt, making it a pop-up contemporary art gallery where promising artists, including Uwadinma, could exhibit.

– Art as a message –

Zina Saro-Wiwa refuses the tag of “activist”, calling it “too flat and too simplistic”.

Oil pollution in Nigeria’s Delta region has become a hot issue, combining corruption, damage to the environment and consequences for health

She also refused to be resigned to the inevitability of oil pollution and conflict between armed militants, oil companies and the government.

Instead, the artist wants to get young people in the Delta to ask questions about their future and their environment through art and performance.

She sees it as a way of telling them: “Don’t expect foreign companies to provide a job for you or to steal oil from them, we have to take charge of us.”