‘They should be embarrassed’: Mpofu slams charges as disciplinary hearing postponed

Living in a hovel metres (yards) away from the so-called “College of Knowledge” where the dreaded strongman trained child soldiers to kill, Duko recalls when times were so much more comfortable.

“I really wish for our former president to be back with us,” Duko says. “In Taylor’s day, at least we were growing.”

Duko’s image of Taylor as a caring, decisive man — he would alter the price of a sack of rice with a simple declaration on the radio — contrasts starkly with the reputation of a man who fuelled conflicts across several countries, leaving hundreds of thousands dead.

But, in Bong county, one man’s war criminal is often another man’s hero. It was from here that Taylor, 69, launched attacks in his rebel days and where his sprawling farm still remains. In his pomp, the county and its people were cossetted.

The man himself is gone, but as key wartime figures and their associates cement a grip on positions of power, prosecutions for Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars in 1989-2003 that killed an estimated 250,000 people are slipping further away, experts say.

A former international football star, George Weah sets his sights on the presidency, with none other than Taylor’s ex-wife Jewel as running mate

Meanwhile Taylor’s ex-wife, Jewel Howard-Taylor, could well become vice-president on the ticket of footballing icon George Weah in a run-off election to be held on December 26, while former rebel leader turned politician Prince Johnson has pledged them his support.

– Taylor ‘did his best’ –

Many families living in Bong county, or in Johnson’s stronghold county of Nimba, lost jobs and protection when Liberia’s civil wars ended. For them, 12 years of living under President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf often compares unfavourably.

Duko, who is supporting a wife and two children on a meagre income, complains that essentials have in some cases tripled in price since the Taylor era.

“He was fighting war and at the same time sustaining the Liberian people,” echoed insurance company employee Eddie Dahn, who lives in the Bong county capital of Gbarnga, explaining how Taylor helped protect Bong and provided employment on his farm.

Dahn said Taylor “did his best” — a view not shared by the international community.

Taylor is currently serving a 50-year sentence for war crimes in a British jail cell, although he was convicted of funding rebel groups in Sierra Leone, not the recruitment of child soldiers, killings, rape and pillaging of which he is accused at home.

“Liberia’s lack of effort and progress in holding to account individuals responsible for horrific human rights violations and war crimes is deeply disappointing,” said Human Rights Watch’s Corinne Dufka, who helped gather evidence that led to Taylor’s prosecution.

– No prosecutions –

Other ghosts from Liberia’s harrowing past sit in the Senate, head major companies, and even preach from the pulpit on Sundays.

Yet not a single sentence for wartime offences has been handed down in the country.

Johnson, who was filmed laughing and drinking beer as his band of ragtag rebels savagely tortured ex-president Samuel Doe to death in 1990, is now a senator, recent presidential candidate, and born-again preacher.

Benoni Urey, another presidential candidate who served as head of the lucrative Bureau of Maritime Affairs during the Taylor presidency, became one of Liberia’s richest men through contracts awarded to his telecoms firm Lonestar Cell.

As Urey himself noted in an interview this year, several ministers in Sirleaf’s cabinets have also served under Taylor. Sirleaf was one of the prominent Liberians abroad who had endorsed Taylor when his ragtag army seized large parts of the country.

Uriah Mitchell, head of programmes and production at Radio Gbarnga, believes the impunity of those involved in the war is holding Liberia back.

“People who really brought down grievous crimes and who were involved in the issue of the war need to be prosecuted,” he told AFP in his stuffy studio, adding that instead they have been “rewarded”.

For all the fuss over Taylor and Johnson’s support of Weah, his rival for the presidency, current Vice-President Joseph Boakai, has received backing from former Taylor associate and telecoms magnate Urey.

– Her own woman? –

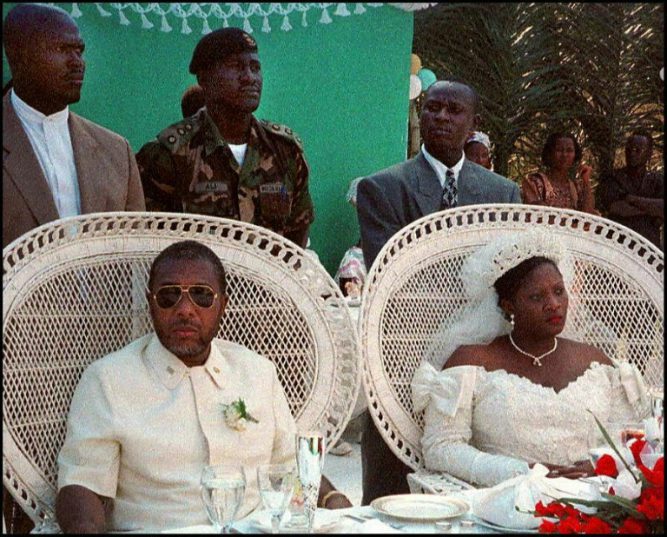

Charles and Jewel Taylor got married in Gbarnga, the former headquarters of the Taylor-led National Patriotic Front of Liberia

The most complex figure in the debate over Liberia’s past and political present is former First Lady Howard-Taylor, who was not in Liberia during the war and has never been accused of any crime but was subject to a UN travel ban that was only lifted in 2012.

She was a surprise vice-presidential pick by Weah, who played professional football throughout the war and returned in the mid-2000s. Weah now says the country “needs to move on” from its obsession with her husband.

Questions over Howard-Taylor and Weah’s ongoing links with Taylor have dogged the election after the former AC Milan ace admitted speaking to him in prison in January.

Regardless, Weah saw a 30-point boost in his numbers in Bong county — the country’s third biggest constituency where Howard-Taylor serves as a senator — during the first round of the election on October 10, compared with his first run for the presidency in 2005.

James Youtee-Mace, chairperson of the Bong County Athletic and Social-Intellectual Center in Gbarnga, said Howard-Taylor had fought to bring money for education and development to the area.

“I think she has done well, that’s why she has been elected twice,” he said defensively.

Download our app