Italy has seen a sharp fall in the number of migrants arriving on its shores, a decline that has left experts scrambling for an explanation.

Summer is traditionally the peak season for migrants attempting the hazardous crossing of the Mediterranean from North Africa to Europe.

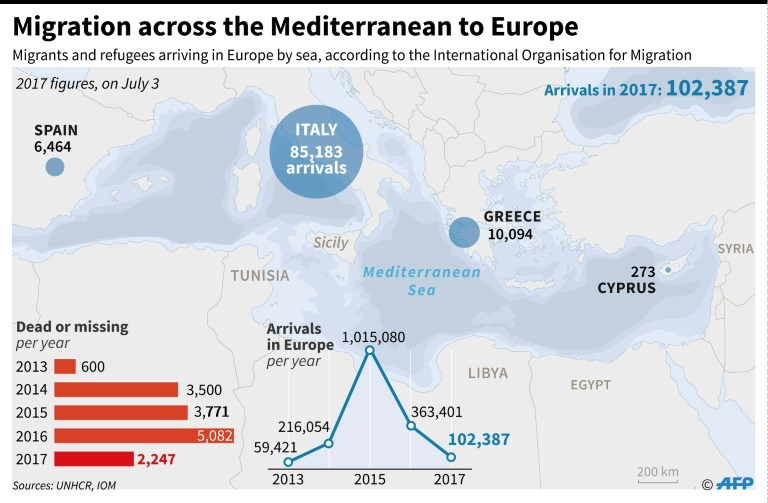

But, to much surprise, only 13,500 have arrived in Italy since July 1, compared to 30,500 over the same period in 2016 — a year-on-year fall of more than 55 percent.

Many migrants are from poor sub-Saharan Africa, fleeing violence in their home country or desperate for a better life in prosperous Europe.

“It’s still too early to talk of a real trend,” cautions Barbara Molinario, a spokeswoman for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

One mooted reason for the fall is tougher action by the Libyan coastguard. The force which has been strengthened by help from the European Union (EU), which trained about 100 personnel over the winter, while Italy has provided patrol vessels, recently supported by Italian warships in Libyan waters.

Migration across the Mediterranean

But according to figures from UN’s International Office of Migration (IOM), the Libyan coastguard have intercepted fewer than 2,000 migrants since early July, compared to more than 4,000 in May.

Another reason put forward to explain the decline is tougher action by NGOs who have been accused by critics of colluding with smugglers to pick up migrants at sea to prevent them from drowning.

But these organisations have been involved in only a fraction of migrant rescues — and three NGO vessels are still operating in the hope of picking up those in need.

– Blocked routes –

For Mussie Zerai, an Eritrean priest who campaigns for migrants in distress, the likelier cause for the decline lies inland.

Agreements between the EU and transiting countries mean “the routes are blocked, the crossing points are more monitored,” Zerai told AFP.

In Sudan, the authorities have said they have beefed up border patrols, but deny reports from humanitarian organisations that they have been using violent militia which have been fighting rebels in Darfur.

“In Libya, the tribes in the south have also sign agreements. The migrants are thrown into nightmarish detention centres in the desert or are turned back,” Zerai said.

In West Africa, awareness campaigns have been launched to try to dissuade young people from making the hazardous trip to Libya, where violence and exploitation await, before they even try the perilous sea crossing.

“We are working very hard back home to discourage our youngsters from trying to cross to Europe by sea,” a Ghanaian community chief who has been in Libya for 26 years said.

“We don’t want them to perish for a dream that may not come true. We talk to them, explain how things really are and let the elders in the villages and the bishops and priests in churches make them promise to be careful if they decide to go to Libya.”

He added: “There are still a lot of Ghanaians in Libya. They are here for work and to send money back home for their families. Many of them decided to return, especially the young ones, with the help of the embassy and the Libyan authorities.”

Fears of the risks in Libya may explain why the number of migrants arriving in Spain, via Morocco, has tripled since the start of the year to 8,200, according to IOM figures.

Molinario said that an EU ban on selling inflatable boats to Libya may also have made life a bit more uncomfortable for smugglers.

Even so, demand is likely to remain high, given that there are still hundreds of thousands of migrants in Libya, who find themselves in a war-torn country and at risk of violence and abduction.

OIM spokesman Flavio di Giacomo suggested that one reason could be conflict between rival smuggling rings, or perhaps a shift in strategy by smugglers to take into account tougher conditions.

But, he acknowledges, “we don’t really know what’s happening”.

The decline in numbers has eased the political pressure resulting from the inflow — but only temporarily.

– Migrant conditions –

Since 2014, 600,000 migrants have landed in Italy, but more than 14,000 have died.

Italian newspapers which, just a few weeks ago, were accusing NGOs of abetting an influx that seemed uncontrollable have now switched to reports on the terrifying conditions faced by migrants in Libya.

“Sending them back to Libya right now means sending than back to Hell,” the deputy foreign minister, Mario Giro, said earlier this month.

Italy is pushing for centres for refugees to be set up in Libya that could provide safety.

“We are working on it, but it’s difficult,” said Molinario. “We need funds, agreements with the authorities and access to the country,” she said. The UNHCR itself had had to withdraw its foreign staff from Libya in 2014.