"Before, we were able to go to work in any mine to dig for diamonds. But today, we're all afraid of dying," artisanal miner Banayi Ilunga says grimly.

Diamonds are the blessing of Kasai, a vast region of five provinces in Democratic Republic of Congo that in many ways holds the key to the country’s future.

To Ilunga, an 11-year mining veteran, the poorly regulated industry offers a lifeline — but in the past year, his hard-scrabble existence has become even tougher.

He has had to abandon the most profitable sites for the safety of mines close to the city of Tshikapa, where the pickings are slim.

But that is the price to pay for staying alive.

Kasai’s year of torment began on August 12, 2016, when security forces killed a local tribal chief, Jean-Prince Mpandi, who was at loggerheads with the state administration and posing a challenge to the rule of President Joseph Kabila.

The death of Mpandi — known by the tribal title of Kamwina Nsapu — and the failure to give him a funeral with rites befitting his status sparked an insurrection, which led to a brutal repression, in which civilians are paying a terrible price.

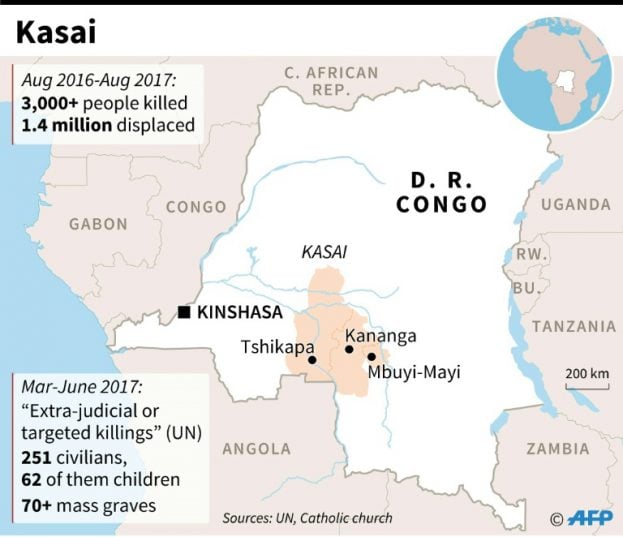

The Roman Catholic Church estimates that more than 3,000 lives have been lost, including those of two experts mandated to investigate the conflict by the United Nations.

Safe but afraid: An Internally Displaced Person (IDP) at a camp in Kikwit

On Friday, the UN gave details of more than 250 “extra-judicial or targeted killings” in Kasai from mid-March to mid-June, including dozens of children. About 1.4 million people have fled the atrocities, many of them to Angola.

In office since he succeeded his murdered father in 2001 while war wracked the nation, Kabila failed to stand down last year at the end of his final elected constitutional term.

A deal was cut by the regime and a minority within the opposition to hold elections by the end of 2017.

But whether the ballot can go ahead may well hang on what happens in Kasai.

– A million people cut off –

Astride the Kasai river weaving its way past palm trees, Tshikapa is home to a million people who are largely cut off from the rest of the world.

They live like a population under siege, for to take to the roads and waterways is to roll the dice with death.

“When the Kamwina Nsapu arrived here in mid-December, a whaler (a light transport vessel) and a speedboat of the provincial government were set on fire,” Mama Ngombe said, referring to a tribal militia of the same name as their leader.

“There is still disorder and killings of passengers.”

River traffic at Tshikapa is almost at a standstill because of the violence

In July, the Association of Navigators of Kasai-Tshikapa (Anakat) temporarily suspended river traffic in protest at the insecurity. Navigation has since resumed warily.

The highways are especially dangerous, and people are advised never to travel alone but in convoy.

The road from Tshikapa to another major town, Kananga, is similarly under the control of the Kamwina Nsapu, according to specialists in the region.

The main road to Kinshasa, meanwhile, is in the grip of Pende militia, from another local tribe.

The enforced isolation has sent prices soaring. In the marketplace, the price of corn, cassava and palm oil has risen by 50, 100 and 150 percent respectively.

– Homeless and burned –

Tshikapa has taken in more than 70,000 people displaced by fighting between security forces and the Kamwina Nsapu, as well as bloody rivalry among communities such as the Luba, Tchokwe and Pende.

One of the displaced, Agnes Mupetu, 37, lost all her six children to the flames when her home was razed. She has visible burn injuries.

“I don’t know how I got out of our house when it was burned down. I woke up in the forest with no medicine. I didn’t even have access to traditional medicines. People picked me up with my wounds in the forest,” said Mupetu. Her husband went missing in the fire.

Food, clothing and health care have been provided for only 30,000 people by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and local NGOs. “We have limited resources,” said local FAO official Moise Muhindo.

A volunteer brings daily food rations for a camp at Kikwit for people displaced by the bloody Kasai conflict

The UN body also provides seeds, hoes, rakes and watering cans to farming families in a bid to help them get agricultural activity going again.

The authorities are keen to emphasise signs of a return to normal life since Kabila visited the troubled Kasai region in mid-June.

Their latest announcement, jointly with Angolan provincial authorities, was that the 31,000 Congolese refugees in Angola can return.

But in the past few weeks, only about 1,400 are estimated to have come home voluntarily.

– Kasai the key –

On the political front, Kasai’s problems weigh heavily on the prospect of stability.

The head of the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), Corneille Nangaa, has said it would be impossible to organise a presidential poll by year’s end, notably because of the region’s insecurity.

Kasai

Speaking to AFP in Tshikapa recently after a new tour of the region, he saw signs of an improvement.

“We think that our action will help bring peace and calm,” Nangaa said.

Launching an electoral census in Kasai — a vital first step — could begin, he said. But he mentioned no date.