Burundians voted Thursday in a referendum on constitutional reforms that, if passed, will shore up the power of President Pierre Nkurunziza and enable him to rule until 2034.

President Pierre Nkurunziza's run for a controversial third term in 2015 plunged Burundi into a deadly political crisis

Police, soldiers and armoured vehicles were out in full force for the referendum, which comes three years after Nkurunziza sought a controversial third term, triggering a political crisis that has killed 1 200 and forced 400 000 from their homes.

Hundreds of people lined up for the vote in which they are merely asked to decide yes or no (“Ego” and “Oya” in Kirundi) in the “constitutional referendum of May 2018”, with no question posed on the ballot.

“Long lines have been seen at the opening of polling stations in Bujumbura. Burundian citizens were impatient to go and vote,” presidential spokesman Willy Nyamitwe wrote on Twitter.

An AFP photographer also reported long lines at polling stations in northern Burundi.

“I came at dawn because I was impatient to vote ‘yes’ to consolidate the independence and sovereignty of our country,” said a farmer, who gave his name only as Miburo, in the town of Ngozi.

Nkurunziza, dressed in an Adidas tracksuit and orange bush hat with a chin strap, queued from 6am (0400GMT) to cast his ballot, praising the population for turning out to vote “en masse”.

Hundreds of Burundians lined up for the vote in which they are merely asked to decide yes or no. AFP/STR

Campaign of Terror

The changes will be adopted if more than 50 percent of cast ballots are in favour.

But with opponents cowed and exiled, there seems little doubt the amendments will pass, enabling the 54-year-old Nkurunziza – in power since 2005 – to remain in charge for another 16 years.

The campaign period, like the preceding three years of unrest, has been marked by intimidation and abuse, say human rights groups.

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) said there had been “a campaign of terror to force Burundians to vote yes”.

Witnesses told AFP that in some parts of the capital and countryside, members of the feared youth militia Imbonerakure – accused by rights groups of atrocities during the political crisis – were going door to door ordering people to polling stations to vote.

Some 4.8 million people, or a little under half the population, have signed up to vote, according to the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI).

While the exiled opposition group CNARED has called for a boycott of the vote, Nkurunziza’s main opponent inside Burundi, former rebel Agathon Rwasa, has called his supporters to vote no.

A presidential decree ruled earlier this month that anyone advising voters to boycott the vote risks up to three years in jail.

No international observers are keeping an eye on the vote, and the majority of foreign correspondents were prevented from entering the country due to administrative hurdles.

Earlier this month Burundi’s press regulator suspended broadcasts by the BBC and Voice of America (VOA) and warned other radio stations, including Radio France International (RFI), against spreading “tendentious and misleading” information.

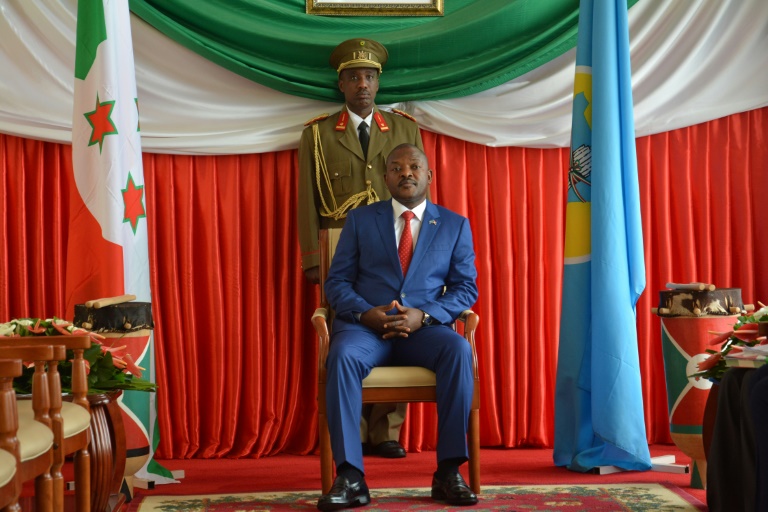

Burundi President Pierre Nkurunziza, seen here in a June 29, 2017 picture, faces sharp criticism at the United Nations for seeking to hold on to power for another term

Fragile peace at risk

For many critics, the referendum is yet another blow to hopes of lasting peace in the fledgling democracy, which experienced decades of conflict marked by violence between majority Hutu and the minority Tutsi, who had long held power.

Decades of sporadic violence exploded in 1993 after the assassination of the country’s first Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye, marking the start of a civil war that would last until 2006 and leave more than 300 000 dead.

A peace deal, signed in the Tanzanian city of Arusha in 2000, paved the way to ending the fighting and included a provision that no leader could serve more than two five-year terms.

Nkurunziza’s third term circumvented that clause and the proposed constitutional amendments will abolish it, increasing terms to seven years and allowing Nkurunziza to stand again in 2020.

Other reforms allow the revision of ethnic quotas seen as crucial to peace after the war and shift powers from the government to the president.

“The Arusha Accord is not only about ethnic quotas, but also measures that ensured the respect of political minorities, the sharing of power but also limiting the power of the majority,” said Thierry Vircoulon, a researcher with the French Institute of International Relations.

Download our app