Recipe of the day: Warm winter Sishebo Beef Curry

Uncertainty over the future arrangements for exporting horses to Britain, its main market, has sparked frustration and anger in a sector worth more than 1.8 billion euros ($2.1 billion) to the economy, and which supports almost 30,000 jobs.

“It is a huge employer in the countryside, so anything that damages it is something to be really worried about,” said Harry McCalmont, whose Norelands Stud is a prominent middle market breeder.

Talk of Brexit dominated last week’s foal and breeding stock sales at Goffs, Ireland’s premier public auction house, where buyers from across the world spent 41 million euros.

The tone was set by a foal by star Irish-based stallion Galileo, which sparked a bidding war before the auctioneer’s gavel finally fell at the princely sum of 1.1 million euros to an agent acting for an unnamed US buyer.

However, short-term joy about the lively trade could not blow away worries over what lies ahead.

McCalmont said that Brexit would nullify the tripartite agreement that exists between Ireland, England and France over the free movement of horses.

Once Britain leaves the EU’s single market and customs union, horses could be subject to passport controls and delays at the border unless some new agreement is reached.

Pointers react to bids in the sale arena at the November horse breeding stock sale at Goffs, Ireland’s premier public auction house, in Kill, County Kildare

“We don’t envisage any change between Ireland and France but the problem is we have to travel through England (to keep the journey manageable) so if there is a hard border there will be an enormous amount of paperwork, red tape, maybe tariffs,” McCalmont told AFP.

Figures compiled by auditors Deloitte showed Ireland sold horses worth 169 million euros to England in 2016 — 50 percent of the total sales at public auction of Irish bloodstock.

“While Ireland arguably currently has a leadership position within Europe, its pre-eminence is not guaranteed,” they warned in a report released last month.

– ‘Punch above our weight’ –

Ireland is proud of its status in the Sport of Kings, and thousands of Irish enthusiasts make the pilgrimage every March to the Cheltenham National Hunt Festival in southwest England, where Ireland’s best jump horses take on the best of the English.

Talk of Brexit dominated last week’s foal and breeding stock sales at Goffs, Ireland’s premier public auction house, where buyers from across the world spent 41 million euros.

“It brings us a lot of prestige; we are the third-largest producer of thoroughbred foals in the world and we punch well above our weight,” McCalmont said.

But he warned: “Bigger operations might move and sell under the British banner but it is the smaller operations and people employed in the countryside who are going to get hurt by this.”

His concerns are shared by Goffs chief executive Henry Beeby, who is angry with the lack of clarity from the British government.

“I think there is a universal feeling of frustration and irritation,” said Beeby.

“It is the fear of the unknown.

“The people who led the Brexit campaign really didn’t have a concise plan and I am pretty doubtful they have one now.”

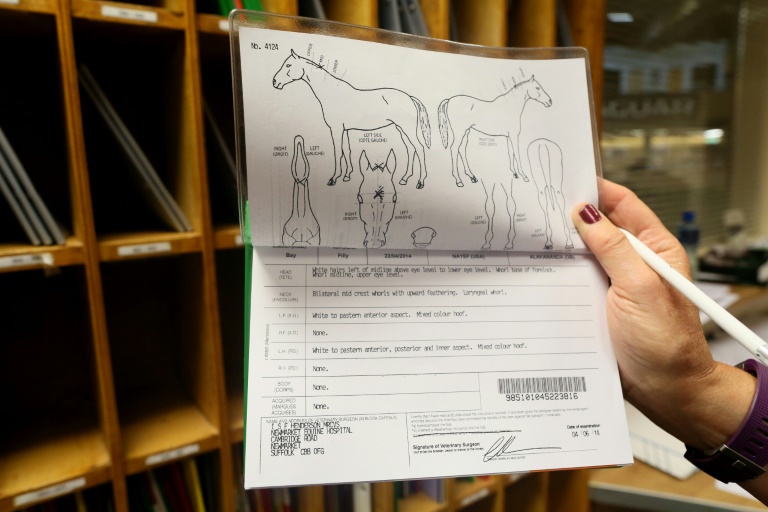

A woman holds a horse passport at the November horse breeding stock sale at Goffs, Ireland’s premier public auction house, in Kill, County Kildare

Beeby, who has been in his present role for 10 years, believes the British industry will suffer as well.

“They cannot be served by just the foal crop in England as they don’t produce enough horses. They need imports and the majority come from Ireland,” he said.

In 2016, some 9,344 foals were born in Ireland compared to 4,663 in Britain.

Beeby, who has raised such concerns with Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar and the country’s agriculture minister this year, agreed that middle market breeders would suffer.

“If you look at the Irish breeder, the majority would fall into the small man bracket. The majority have one or two mares and they are going to get hurt,” he said.

For Irish training great John Oxx, who has twice landed the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, Europe’s most prestigious horse race, it is a pivotal moment for the industry.

“We have seen decades of closer and closer co-operation and the simplification of the rules to do with racing and breeding and now we are looking at the possibility of a backward step,” the 67-year-old told AFP.