Search for Malaysia’s long missing MH370 suspended

Mohammad was eight years old on January 8, 1978 and visiting the mosque with his father in front of the Fatima Masumeh shrine — one of the holiest sites in Iran.

Then something shocking happened: a senior cleric took off his turban and threw it on the ground in disgust.

The reason behind this symbolic gesture — one reserved for displaying only the most grievous offence — was the publication of an article the day before against Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who would soon lead the country into an Islamic revolution.

“He was angry that they had insulted our source of emulation,” says Mohammad, now a sweet seller.

Each Shiite Muslim must choose an ayatollah as his “source of emulation” — and many in Iran had chosen the politically radical Khomeini, who by then had spent 13 years in exile for his scathing attacks on shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the United States.

The article in government newspaper Ettelaat had accused Khomeini of being a British agent, in league with communists, and insinuated that he was not really Iranian and that his religious credentials were questionable.

It is often seen as the moment that sparked the revolution 40 years ago.

Iran’s Islamic rulers have many commemorations planned for the anniversary as they flaunt the unlikely survival of a regime that has often been written off by analysts and opponents, but which once again saw off a major bout of unrest in recent days.

– ‘Provocation’ –

Ayatollah Seyyed Hossein Mousavi Tabrizi, a former chief prosecutor and two-time parliamentarian, was a teacher in one of Qom’s many seminaries — “hawzats” — when he first heard about the article.

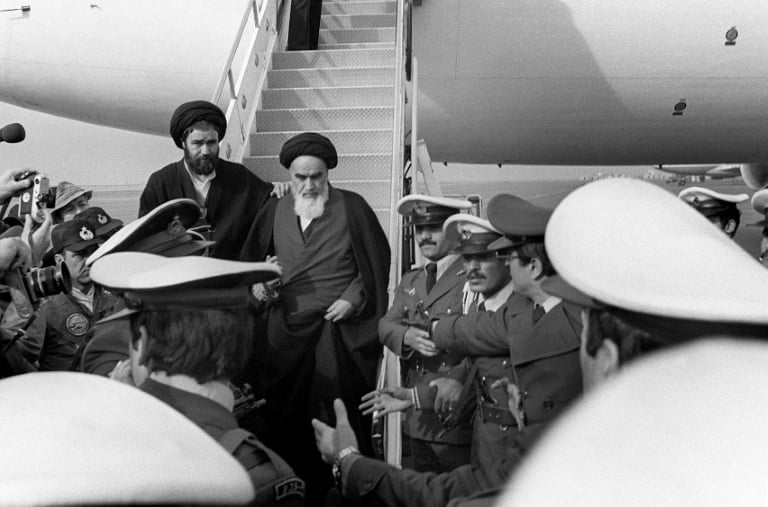

This file photo taken on February 01, 1979 at Tehran airport shows Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini leaving the Air France Boeing 747 jumbo that flew him back from exile in France to Tehran

“It was around 7:00 pm when two or three of my students came to me, very angry, with a copy of Ettelaat and told me to read the article,” he told AFP in Qom, where he has gone back to teaching.

“It was the last straw. Insulting Khomeini like that, saying he was a pawn of the British and other offences — it was an insult to the whole clergy. It was a provocation.”

Although Iran’s Islamic rulers focus most of their ire on the United States these days, many Iranians still reserve a particular suspicion for the British in memory of their colonial machinations in the early 20th century.

Qom’s clerics quickly organised a response.

That same night, a dozen senior clerics gathered at the home of Tabrizi’s father-in-law, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Nouri Hamedani.

“It was decided to stop classes the next day as a sign of protest,” he said — a rare move in a place that prized education so highly.

The strike by students on January 8 saw minor clashes with police. It grew the following day and gathered support from merchants in the bazaar who joined the shutdown.

Soon the protests were widespread, with people chanting slogans against the monarchy and the government.

The spark had been thrown into the tinder box of grievances that had been building for years over growing social inequality, hatred of the brutish security services and an increasing Westernisation that had scandalised the country’s religious conservatives.

– ‘Several dead’ –

Abolfazl Soleimani, a white-turbaned cleric in Qom, was 24 at the time and remembers the scene at Eram Square, now called Shohada (Martyrs’) Square.

“The police opened fire, first in the air I think, and then into the crowd, at the religious, the non-religious, the bazaaris (merchants). There were several dead and injured,” he told AFP.

Historians have since questioned the original death toll of 20-30, with British historian Michael Axworthy saying “there were no more than five” in his book “Revolutionary Iran”.

Women take selfies near the Massoumeh shrine in Qom, where police opened fire on demonstrators 40 years ago

Either way, news of the shootings in Qom swept across the country and set in train a cycle of unrest that would ultimately lead to the downfall of the shah little more than a year later.

Conforming with Shiite tradition, mourning ceremonies were held for the dead 40 days later — on February 18 — providing a pretext for fresh protests against the shah in several cities.

In Tabriz in northwestern Iran, those protests quickly degenerated, with police firing on the crowd and killing some 30 people.

And so 40 days later came further ceremonies that turned angry, in turn sparking more protests 40 days after that.

The authorities managed to calm things down by June, but the ball was already rolling, and the second half of 1978 saw escalating unrest.

“All repressive regimes dig their own graves,” said Ayatollah Tabrizi.

On January 16, 1979, the shah left Iran, never to return.

Ayatollah Khomeini made a triumphant return to Iran the following month and the last government of imperial Iran was soon at an end.

Download our app