A landmark free trade deal linking EU and Canada went into effect on Thursday despite lingering opposition from activists worried about the pact's consequences on the environment and health.

The EU is hailing the deal as one of its most ambitious ever that will set a new standard for future deals, including with Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

Observers have said the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) could set a model for future ties between Britain and the EU after Brexit.

The EU and Canada formally signed the landmark free trade deal, which was seven years in the making, in October last year after overcoming last-minute resistance from a small Belgian region that nearly torpedoed the entire agreement.

“This agreement encapsulates what we want our trade policy to be — an instrument for growth that benefits European companies and citizens,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said in a statement.

However, it is “also a tool to project our values, harness globalisation and shape global trade rules,” he added.

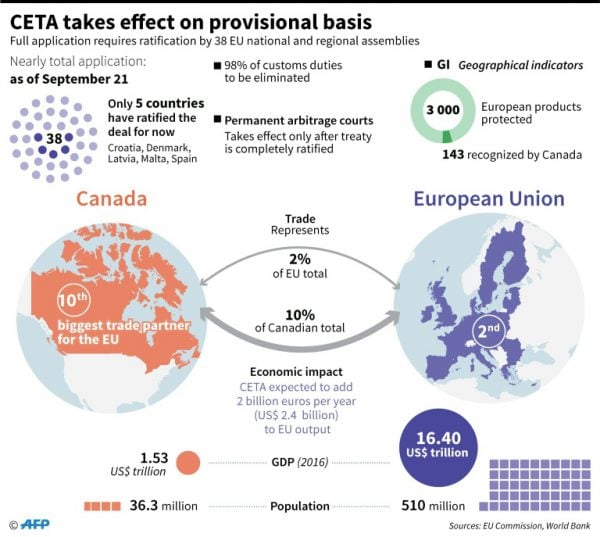

Main points of the CETA free trade deal between the European Union and Canada, which goes into effect on a provisional basis today

CETA has been implemented on a provisional basis pending approval by the EU’s more than 30 national and regional parliaments, which could take years.

The pact affects 510 million European consumers and 35 million Canadians and even provisionally, eliminated customs duties between Europe and Canada on 98 percent of products as of Thursday.

– ‘Unacceptable’ –

Left out of the deal until the end of the ratification process is a controversial investment protection scheme, a usual component of international trade deals.

Under the scheme, companies have recourse to legal arbitration if they believe their rights have been violated by a change in government policy.

This provision raised huge concerns among activists groups that fear the rollback of European regulation on the environment and health if faced with the opposition of powerful multinationals.

“It is unacceptable for CETA to come into force before national parliaments have had their say,” said Greenpeace trade campaigner Kees Kodde.

“Canada has weaker food safety and labelling standards than the EU, and industrial agriculture more heavily dependent on pesticides and GM crops,” he added.

It was these concerns that led the Belgian region of Wallonia, with a population of 3.6 million, to hold up the deal until it won concessions for its farmers.

It also demanded guarantees that the investor scheme face further legal scrutiny by the European Court of Justice, the EU’s top court. That opinion is still pending.

Activists’ anger intensified over CETA when the EU embarked on an even larger — and more controversial — deal between the EU and the United States.

Negotiations for that deal, known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have however frozen since the election of Donald Trump, who reached the US presidency on an staunchly anti-globalisation platform.