A score of mostly wealthy nations banded together at UN climate talks Thursday to swear off coal-fired power, a key driver of global warming and air pollution.

To cap global warming at “well under” two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) — the planet-saving target in the 196-nation Paris Agreement — coal must be phased out in developed countries by 2030, and “by no later than 2050 in the rest of the world,” they said in a declaration.

The dirtiest of fossil fuels still generates 40 percent of the world’s electricity, and none of the countries that truly depend on it were on hand to take the “no coal” pledge.

One country participating in the 12-day talks, which end Friday, has made a point of promoting the development of “clean fossil fuels”: the United States.

The near-pariah status of coal at the UN negotiations was in evidence earlier in the week when an event featuring White House officials and energy executives was greeted with protests.

The US position “is only controversial if we choose to bury our heads in the sand and ignore the realities of the global energy system,” countered George David Banks, a special energy and environment assistant to US President Donald Trump.

Led by ministers from Britain and Canada, the “Powering Past Coal Alliance” committed to phasing out CO2-belching coal power, and a moratorium on new plants that lack the technology to capture emissions before they reach the atmosphere.

“In a few short years, we have almost entirely reduced our reliance on coal,” said British Minister of State Claire Perry.

The share of electricity generated by coal in Britain dropped from 40 percent in July 2012 to two percent in July of this year, she noted.

Other signatories included Austria, Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands and New Zealand.

Germany — where coal powers 40 percent of the country’s electricity — was asked to join, said environment minister Barbara Hendricks.

“I asked them to understand that we can’t make a decision like that before forming a new government,” she told journalists.

Most of the enlisted countries don’t have far to go to complete a phase-out.

Deadlines range from 2022 for France, which has four coal-fired plants in operation, to 2025 for Britain, where eight such power stations are still running, and 2030 for the Netherlands.

– No economic rationale –

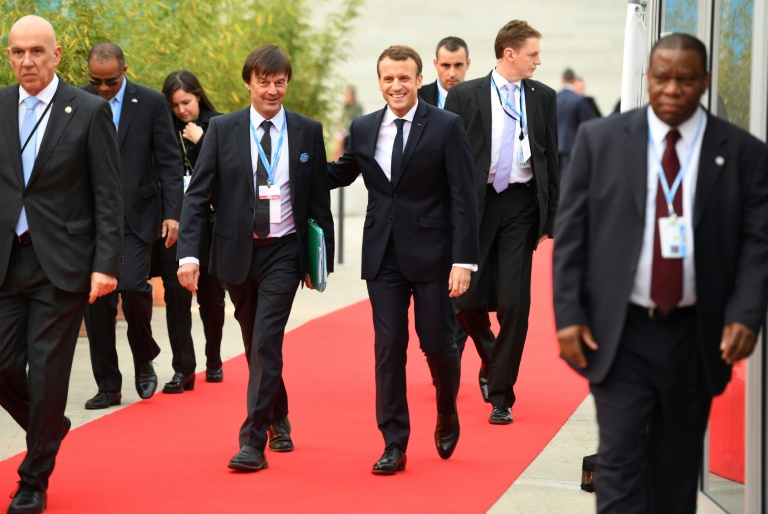

French President Emmanuel Macron (C-R) and French Minister for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition Nicolas Hulot (C-L) arrive to attend the UN conference on climate change (COP23) on November 15, 2017 in Bonn, western Germany

“This climate meeting has seen Donald Trump trying to perversely promote coal,” said Mohamed Adow, top Climate analyst at Christian Aid, which advocated for the interests of poor countries.

“But it will finish with the UK, Canada and a host of other countries signalling the death knell of the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel in their countries.”

But not all countries are in the same boat, said Benjamin Sporton, president of the World Coal Association.

“There are 24 nations that have included a role for low-emissions coal technology as part of their NDCs,” or nationally determined contributions, the voluntary greenhouse gas cuts pledged under the Paris treaty.

Coal continues to play a major role in powering the Chinese economy, and will see “big increases in India and Southeast Asia,” he told AFP.

Making coal “clean”, Sporton acknowledged, depends on the massive expansion of a technology called carbon capture and storage (CCS), in which CO2 emitted when coal is burned is syphoned off and stored in the ground.

The UN’s climate science panel, and the International Energy Agency, both say that staying under the 2 C temperature threshold will require deploying CCS.

The problem is that — despite decades of development — very little CO2 is being captured in this way.

There are only 20 CCS plants in the world that stock at least one million tonnes of CO2 per year, a relatively insignificant amount given the scope of the problem.

One reason is the price tag: it costs about a billion dollars (900,000 euros) to fit CCS technology to a large-scale, coal-fired plant.

“If you could develop cost-effective technology that would be permanent and work at scale, it could be a real game-changer,” said Alden Meyer, a climate analyst at the Washington-based Union of Concerned Scientists.

“But you have to be realistic about the prospects.”

At the same time, the price of wind and especially solar power has dropped so much that CCS may no longer be economical.

The crucial issue is not retro-fitting old plants, but avoiding the construction of new ones, Meyer added.

“There’s really no economic rationale for coal, and there’s certainly no environmental rationale for it,” he told AFP.

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.