Load shedding returns: Eskom announces power cuts for Saturday night

“I do it because no one else in my family can. Both my parents are sick. They cannot move without assistance,” the Rohingya girl told AFP while chopping vegetables in her family’s tarpaulin shanty in Bangladesh.

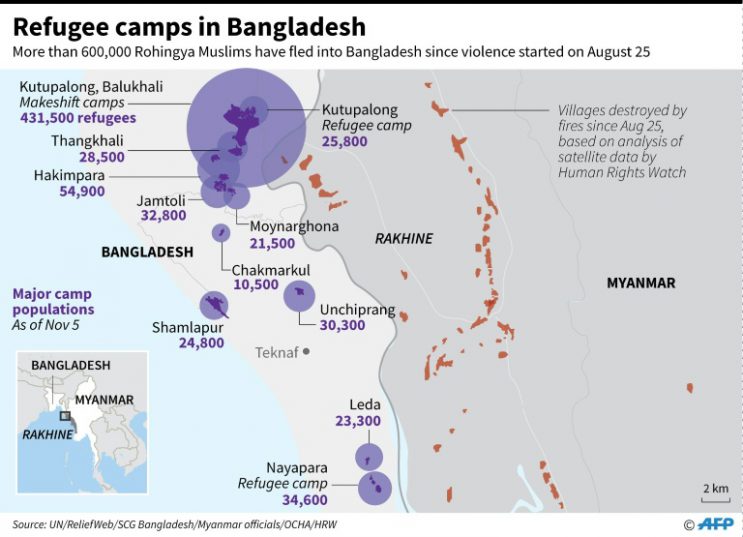

An estimated 1,400 children are sole providers for their families in crowded refugee camps along the Bangladesh border, where more than 600,000 Rohingya Muslims have sought sanctuary from violence in Myanmar since August.

Charities fear they are especially vulnerable to illness and emotional stress from shouldering such responsibility, or exploitation as they struggle to provide for their families in the overstretched tent cities.

Refugee camps in Bangladesh

“This may lead them to child labour and explicit sex work. These families may also experience a spike in child marriages, which is very concerning,” said Save the Children International spokesman Rik Goverde.

For Tahera, who was caring for her infirm parents even before they made the difficult journey from Myanmar, the day starts at sunrise with a long trek into the forest to gather firewood for cooking.

It’s an arduous slog carrying the heavy load back to the family tent, a plastic sheet strung across a bamboo frame on a crowded hillside in Balukhali.

But she barely rests before embarking on her second early-morning chore — jostling with other refugees to fill an urn at the single water pump in her corner of the camps.

The sight of children carting water jugs or dragging sacks of grain is not uncommon in the camps

Later in the day, Tahera carries what’s left of the lumber to the local market to trade for basic supplies.

The refugee influx over the past two months has sent prices skyrocketing, so the little girl must barter hard alongside adults for food and other bare essentials to feed her family and earn money for medicine.

“All my siblings are younger than me. Being the eldest, I am just doing my part,” she said.

– Childhoods lost –

The sight of children carting water jugs, queueing at relief stations or dragging sacks of grain the size of their own bodies is not uncommon in the Rohingya camps.

More than half of the 607,000 new arrivals are children, and aid groups say they are bearing the brunt of Asia’s worst refugee crisis in decades.

A full 7.5 percent of the children crammed into one of the camps in Cox’s Bazar district are at risk of dying from severe acute malnutrition, the United Nations warned last week.

Schools run by aid groups offer some respite to children in the camps

Meanwhile an estimated 40,000 children have crossed the border completely alone, their parents killed or displaced by violence in Myanmar the United Nations has likened to ethnic cleansing.

To survive such horror only to become sole provider for a family is “something that no child in the world should ever experience”, said UNICEF Bangladesh’s spokesman Sakil Faizullah.

Schools and safe zones run by aid groups offer some respite from horrific memories and the grim reality of life in the camps, where many children are forced to care for sick or injured parents and traumatised siblings.

In these child-friendly spaces, youngsters can draw, sing and play in a classroom-like setting away from the misery awaiting them back in their shanties.

Tahera’s younger sister occasionally drags her along to a UNICEF kid’s zone, where she gazes longingly at the picture books available.

But she can never linger long, with her bed-ridden parents and younger siblings relying on her for survival.

“I love the comic book pages. But I don’t get the chance to go there everyday,” Tahera said, preparing a simple meal in the family’s dimly-lit hut.

Bangladeshi charity worker Baby Barua was shocked to learn from Tahera’s younger sister that she was feeding and caring for a family of seven on her own.

“She’s only a kid. She shouldn’t be doing all these (tasks) by herself. This is equivalent to child labour,” Barua said.

Charities are considering cash assistance to lighten the load for young breadwinners, but the need is huge and the scale of the crisis is overwhelming already stretched aid organisations.

Despite the magnitude of the task ahead of them, aid workers say the youngest victims of the crisis must not be forgotten.

“They’ve already lost their childhood and it’s our responsibility to make sure that they don’t lose their future,” UNICEF’s Faizullah told AFP.

Download our app