President Donald Trump has opened the door to the deployment to Afghanistan of thousands more US troops, in his first speech outlining American policy after nearly 16 years of grinding war.

Reversing course from an earlier assertion that he would end US involvement in a conflict that has cost thousands of lives and trillions of dollars, Trump also hit out at neighbouring Pakistan, which he said was offering safe haven to “agents of chaos”.

Here are some key questions about the impact Trump’s strategy could have in a country known as “the graveyard of empires”.

What has Trump announced?

He refused to give figures or details. But the strategy appears to amount to around 4,000 new troops, largely freed from Obama-era restrictions and thus able to take on greater frontline combat roles to target “terrorist and criminal networks”.

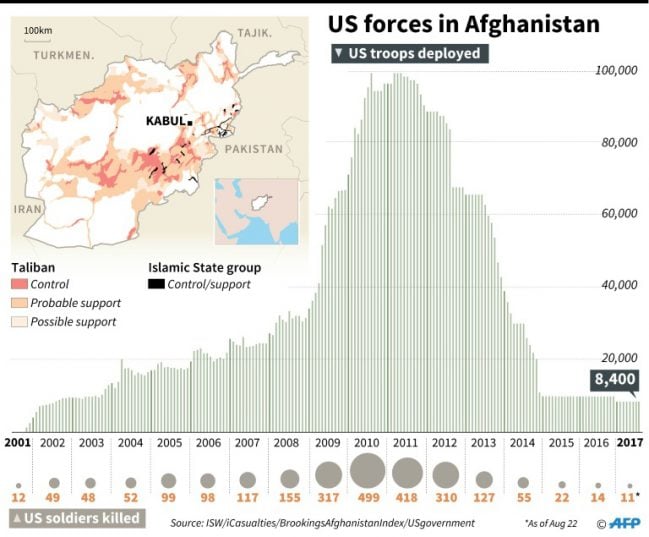

The 8,500 US personnel currently in-country are largely restricted to NATO’s mission of training the Afghan Army and offering strategic support on certain missions, though some are already conducting frontline operations.

The other main plank of Trump’s outline strategy was to pressure Pakistan, a move which has already been attempted repeatedly attempted by Washington.

Analysts point out that US administrations have for years complained that Islamabad talks a good game about helping to defeat extremists, but in fact offers refuge to the Afghan Taliban in particular, and stokes the insurgency.

Will more boots on the ground make a difference?

Not on the face of it. Former President Barack Obama authorised a massive surge that saw troop numbers top out at over 100,000, a move that decreased violence but did not result in a decisive blow.

US forces in Afghanistan

If the might of the US military could not defeat the militants then, many analysts argue that 12,500 are unlikely to secure a lasting victory.

“Probably the greatest contradiction that emerged from (the speech) is the claim we will learn from history and yet none of the policies have not been tried before,” said James Der Derian of the Centre for International Security Studies at the University of Sydney.

Others point out however that Afghan forces are now at a point where a smaller number of advisers more strategically deployed could make a difference.

How will the Taliban react?

With predictable violence and from a position of relative strength, observers say.

They are likely to seek to send an early message, perhaps with a major urban attack — the like of which they proved themselves capable with a massive truck bomb in Kabul’s diplomatic quarter in May.

“The Taliban and other belligerents are likely to respond with a new wave of violence across the country,” including in urban areas, said Javid Ahmad from West Point’s Modern War Institute.

The Taliban has strengthened in recent years, and Afghan forces, beset by spiralling casualties, have struggled to contain them since NATO ended its combat mission in 2014.

A US watchdog says Afghan forces control less than 60 percent of the country, with the rest either in Taliban hands or being violently contested.

Unlike the war-weary United States, the Taliban has an almost endless capacity to absorb loss of life among its ranks.

Nor does the group need — as Washington does — to “win” a grinding conflict that US commanders have described as a “stalemate”.

“(The militants) can wait out another 4,000 troops. The Taliban have survived much worse,” said Der Derian, echoing a proverb long attributed to the Taliban about the war: “You may have the watches, but we have the time”.

Will the pressure on Pakistan work?

Trump returned to the theme that has been a near-constant refrain from Washington since shortly after the 9/11 attacks: Pakistan must stop supporting extremists.

With its long, porous border and poorly policed tribal areas, Pakistan makes a near-perfect refuge for Taliban, out of the range of Afghanistan’s under-performing army and its American protectors.

Despite being a signed-up ally in the US “War on Terror”, Pakistan stands accused of fuelling the insurgency next door, in part as a bulwark against the influence of India — a modern-day “Great Game” reminiscent of the imperial rivalry between Britain and Russia in the 19th century.

Years of pressure from Washington have not changed Pakistani policy, and experts say that sharp words from political neophyte Trump are unlikely to make much difference.

“Pakistan’s enemy is India and it sees India as an existential threat, and Pakistan believes that the Taliban and the Haqqani network can help keep India at bay in Afghanistan,” said Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center in Washington.

“No matter what threat or punishment the US throws at Pakistan, Pakistan is not going to change these ironclad, immutable strategic interests.”

pdh-ds-amj-st/hg/sls

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.