It has been said that deep human attraction is often premised on our scents.

During steamy days, a body’s physiological response may cause you to wrinkle your nose: the smell of what many people associate with sweat.

In reality, sweat itself doesn’t have much scent. Surprisingly, the distinctive smell of human sweat results from a cocktail of microorganisms, living in and on our bodies, that metabolize sweat into body odour. Bacteria not only inhabit humans but, in some respects, define us because they play such an important role in our health. Who we are as individuals may have a great deal to do with our personal collection of bacteria.

I’m an artist who focuses on science. I became intrigued by sweat after considering the implications of the human microbiome, the hundreds of microorganisms that inhabit our bodies.

For the last five years, I have worked on an elaborate scent-based art installation called “Labor” to recreate the odour many people associate with sweat and give audiences a new way to “see” and understand smell. My art installation focuses on bodily secretions, bacteria that create odour and how those scents shape our perceptions of ourselves and each other.

Work and sweat. Cause and effect

There is an unusual laboratory in Helsinki, Finland, founded to host creative interdisciplinary practices called “bio-art.” As part of an artist’s residency, I worked at Biofilia at Aalto University to recreate the scent people associate with sweat. For inspiration and perspiration, I used myself as a laboratory subject, spending plenty of time in the legendary Finnish saunas.

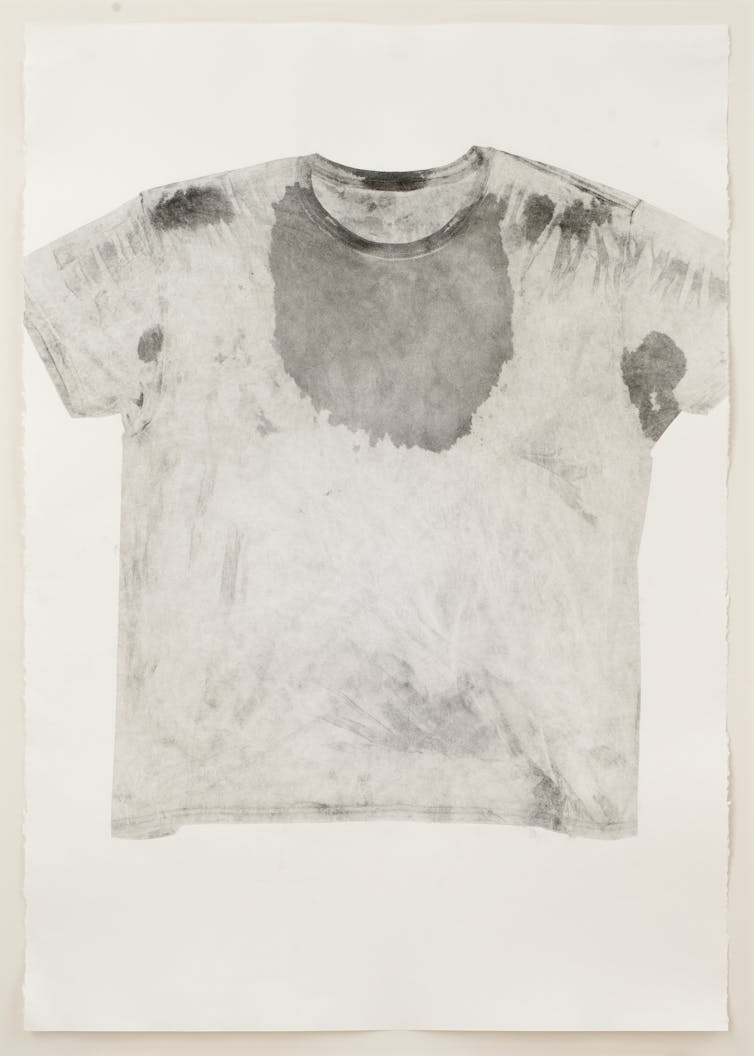

Burchfield Penny Art Center. Photo by Tullis Johnson., Author provided

In the human body, bacterial cells far outnumber human cells. They fill our guts, enable digestion, affect immune reactions and influence appetites and emotional states.

Specific bacteria metabolize sweat to produce an aroma or scent that results from warm temperatures, stress or physical effort. Sweat is a smell that can signal work, such as toiling in a “sweatshop,” or hard manual labor made even harder by poor working conditions. Idioms like “by the sweat of one’s brow” or “sweat equity” are some of the ways we define work, even as work can define us and provide a sense of self-worth.

During the Industrial Revolution, machines began to replace human workers in factories. More recently, microbes have begun to replace and augment these machines. Today, microbes are used to produce a wide range of products including enzymes, foods, beverages, feedstocks, fuels and pharmaceuticals.

Three genus of bacteria are key in producing human scent – Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium. These bacteria metabolize sweat, a human byproduct, to produce a waste product, which has a distinct odour. Two types of glands – eccrine and apocrine – produce sweat. Eccrine glands excrete a fluid, mainly water and salt, that helps to regulate body temperature. Apocrine glands excrete a denser, milky fluid often resulting from emotional stress. It is the bacterial breakdown of apocrine sweat that produces the most pungent body odours.

Staphylococcus transforms amino acids in sweat into various acids, a smell I describe as “high-pitched,” or the dirty sock smell of a locker room.

Corynebacteria alters scentless human steroids and other molecules in sweat to produce smelly steroids and sulfur compounds. I affectionately named these odours “white-collar labor.” Likewise, Propionibacterium metabolize amino acids to produce an acrid odour, funky and vinegary.

The art and science of smell

My research began by defining human skin bacteria associated with odours and learning how to grow them. The scientific literature is sparse, as much of this research is carried out by deodorant and antiperspirant industries, which often don’t publish their results.

Next, I isolated my sweat by capturing bacteria from my armpits in sterile gauze, filtering it and incubating it in dozens of heat and atmospheric conditions. Then I designed a bioreactor, similar to fermenters that brew beer, except they are built to enable more varied types of biochemical reactions with microbes. Finally, I experimented with liquid cultures that encouraged bacteria to thrive and produce fragrant waste products.

The concept of my artwork “Labor” is that microorganisms create the “vulgar odours” of sweat, a byproduct of production and labor reminiscent of “sweatshops” and factories of the 19th and 20th centuries. The exhibit contains several large glass bioreactors, each populated with one of three strains of bacteria. The soup in each container produced the smell of sweat, odours that collected in a central glass enclosure where a white T-shirt hung. From there, the smell drifted into the room.

The complexity of human aroma

After five years working with skin bacteria, I am only beginning to fathom the complexity of human aroma.

Tullis Johnson, Author provided

For instance, while three main strains of bacteria may be responsible for the most common smells of sweat, it would be simplistic to imagine this is the end of the story. Many bacteria have a variety of metabolic options to thrive, and each produces different byproducts and chemical compounds. Some stink, some don’t. How do they interact together and with other bacteria or fungi on the skin to produce our distinct smell?

It has been said that deep human attraction is often premised on our scents. If bacteria are responsible for our scent, then are we attracted to a person or their bacteria? Perhaps bacteria help steer human sexual selection and evolution.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]

Paul Vanouse, Professor of Art, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For more news your way, download The Citizen’s app for iOS and Android.

Download our app