For decades, she was thought to have started out as a man.

But a sketch uncovered at an obscure Parisian auction in 2012 triggered groundbreaking research that revealed the original painting beneath Jean-Honore Fragonard’s “Young Girl Reading” to be a woman gazing outward.

“The drawing pointed out this likely inaccuracy,” said Michael Swicklik, senior conservator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, adjusting his magnifying glasses to examine the luminous 250-year-old portrait of a girl in a bright lemon dress absorbed in her book.

Swicklik was part of a trio of experts who used techniques akin to those NASA deployed on its Mars rovers to dispel any doubt the work belonged to a boldly experimental series by a young Fragonard, just coming into his own two decades before the French Revolution.

There is no significant record from the period of the artist’s legendary “Fantasy Figures,” created around 1769, which Paris Louvre senior curator Guillaume Faroult described to AFP as “one of the absolute masterpieces in the history of painting.”

Even less was known about “Young Girl Reading,” whose profile view had relegated her to the periphery of the series.

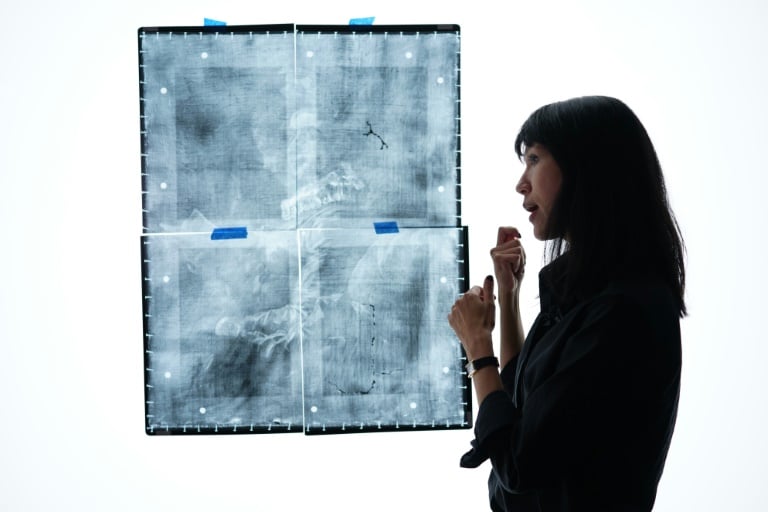

“Young Girl Reading” by Jean-Honore Fragonard is seen at the National Gallery of Art’s painting conservation studio, where conservators examine and touch up other priceless works

When the painting was restored in 1985, experts erroneously concluded a man lay beneath based on x-ray imaging.

But today, researchers have many more tools at their disposal, and the National Gallery’s team was able to confirm suspicions aroused by the newly discovered sketch of the series.

“That we could actually then re-examine the painting through these new techniques and prove that it was inaccurate and how inaccurate it was, and actually simulate what it looked like, was very exciting for a conservator,” Swicklik said, gesturing at the unframed painting in the museum’s conservation studio as colleagues around him worked on other gems.

– Shrouded in mystery –

The fantasy figures portray members of Fragonard’s social circle dressed in extravagant masquerade style and looking out in engaging, theatrical poses.

Fragonard, known for highly decorative, veiled eroticism in works like “The Swing,” highlighted more minute details here in the women than the men, using the back of his paintbrush to evoke collar creases.

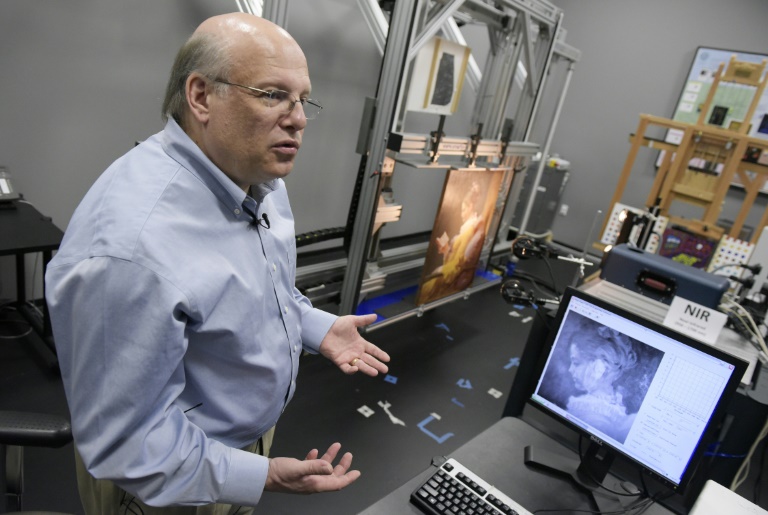

National Gallery of Art senior conservator of paintings Michael Swicklik speaks about “Young Girl Reading”

The girl’s profile view had relegated her to the margins of the series, despite the similar dress, light source and frenetic brushstrokes applied “alla prima” (wet on wet paint) with virtuosic ease and agility.

But the sketched vignette matching the portrait showed the subject facing the viewer.

“It was not a painting about which we imagined making further discoveries,” said Yuriko Jackall, the museum’s 18th century French painting expert who enlisted the help of Swicklik and senior imaging scientist John Delaney.

Fragonard “seems to have made one composition and left it alone for a while, and then come back to it several months or maybe a few years later,” explained Jackall.

“Why did Fragonard make a change like this? Was this because the model rejected the painting and so the painting remained unsold? Was it that the initial painting was almost like a figure study? We are not totally sure.”

– Going in blind –

National Gallery of Art assistant curator of French paintings Yuriko Jackall, next to an x-radiograph of “Young Girl Reading”

Working like a team of detectives, Delaney, Jackall and Swicklik studied a tiny cross-section taken from the painting in the 1980s — the traditional way of observing paint layers — along with three different types of scientific imaging, without ever touching the work.

“You start off this research not knowing what you’re looking for,” said Delaney as he demonstrated a scan of the canvas mounted on a mobile easel at the museum’s chemical imaging lab.

“But you collect many different kinds of information — the canvas weave, the pigment types, the style of the painting, and then you start to see strange things.”

National Gallery of Art senior imaging scientist John Delaney shows XRF imaging spectroscopy of “Young Girl Reading” at the museum’s chemical imaging lab

Delaney and co-researchers developed a pair of custom-built tools: a high sensitivity near infrared hyper spectral imaging camera and an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) imaging sensor.

They also used techniques known as diffuse reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS) and reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), along with high-resolution color photography.

Combined with four sets of carefully calibrated lights, the technologies produced more than 750 highly detailed images of the painting in very narrow wavelength ranges that helped create a realistic simulation of the original composition.

During XRF imaging spectroscopy, mercury analysis clearly revealed the outlined “ghost” of the underlying woman, along with her plumed headdress adorned with pearls.

– The sketch is key –

Delaney shows a picture of “Young Girl Reading” and a simulation of the underlying painting based on technology that split up the image into spectral bands of just a few nanometers wide

At the heart of the research was a faded sheet of paper on which the artist had sketched out 18 distinct thumbnail-sized portraits that corresponded to paintings associated with the fantasy figures.

In addition to unlocking the mystery of “Young Girl Reading,” the sketches also dispelled some long-held assumptions.

Beneath all but the girl’s underlying composition, Fragonard made inscriptions that for the first time associated the portraits with names, though it is still unclear whether they identify patrons or the sitters themselves.

The annotations named previously unidentified portraits for some, revealed mistaken identities for others and left out paintings long considered part of the series.

What had been celebrated as an iconic image of Enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot — a ruthless art critic — is now associated instead with writer Ange Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon.

These and other related findings raise more questions than they answer. Four of the 18 works sketched out are still unknown.

Yet more discoveries possibly await after Jackall curated the first known exhibition entirely devoted to the fantasy figures, running until December 3 at the National Gallery.

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.