Immersive art from a famed desert festival in the American West has swept into Washington, infusing the buttoned-up US capitol with countercultural spirit.

“No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man,” which opens Friday at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, celebrates the annual late-summer gathering that sees a temporary city of some 75,000 people spring up in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

For a single week, massive experiential art installations tower over the dusty metropolis before Burning Man participants torch many of the works, including a giant wooden statue of a man, as a ritual embracing decommodification and temporality.

Thought it is perhaps best known for its bacchanalian atmosphere favoring sex and drugs, the annual event that started small in 1986 has evolved into a serious cultural and artistic movement, said the Renwick’s crafts curator Nora Atkinson, who spearheaded the show.

“Shrumen Lumen” by the Foldhaus Collective is an interactive installation featured in Washington’s Renwick Gallery “Burning Man” exhibition

She pushed to welcome the radical art of the desert to the rarefied environment of the museum because “it really stands out from a lot of the work being done in the contemporary art world,” she said.

She also highlighted the freewheeling show’s location just steps from the White House.

“I think it’s really important at times like this — when the world is so cynical, when people are so at odds — that we have this kind of healing force,” she said. “It’s all about empowering people.”

“We build the world that we want to live in.”

– Visual hedonism –

Though it drew comparisons to predecessors including the anarchic Dadaists and large-scale land art movement, Burning Man is a choice destination for techies from neighboring Silicon Valley looking to unwind.

That’s no coincidence, according to Atkinson, who attended her first Burning Man last year.

“The further we get into our digital sphere the more we sort of strive for that humanity around us,” she told AFP at an exhibition preview, standing in the massive, intricate wooden “Temple” installation that encompasses the museum’s cavernous Grand Salon hall.

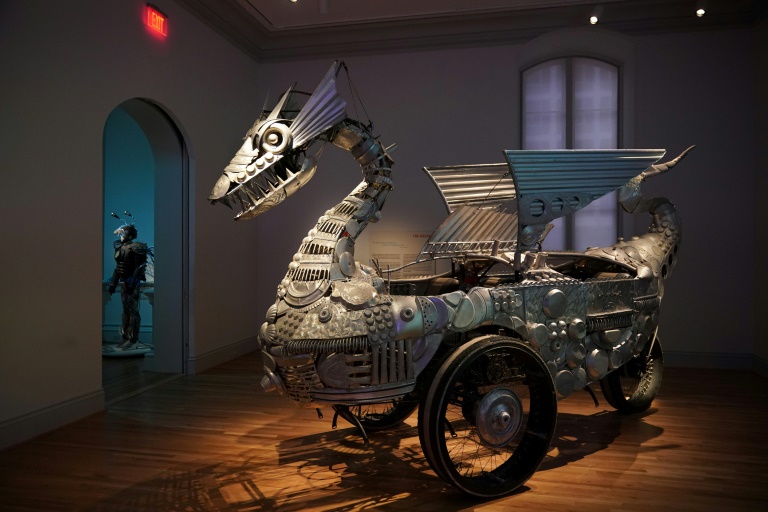

“Tin Pan Dragon” by Duane Flatmo is crafted from reclaimed aluminimum cookware

The show — which follows “The Art of Burning Man” exhibition that went on display at a Virginia museum last year — includes both surviving pieces from past festivals and newly commissioned works.

The visually decadent installations — 14 in the 19th-century era Renwick building and six spilling outdoors into the surrounding neighborhood — featured in the show bridge the worlds of fine art and craft, with a focus on works that make use of reclaimed materials.

“Tin Pan Dragon,” for example, is a dragon-esque vehicle crafted from reclaimed aluminum cookware.

And the 14-foot “Ursa Major” sculpture — one of the several public art pieces installed in the surrounding streets where politicians and lawyers roam — is a grizzly bear fashioned from 170,000 pennies.

– ‘Major’ cultural movement –

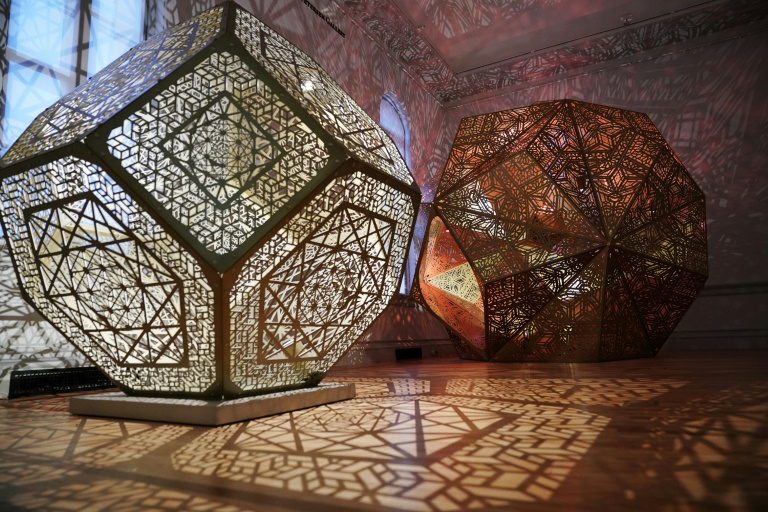

Yelena Filipchuk of the duo behind the “HYBYCOZO” installation of large-scale glowing polyhedrons with elaborate laser cut-outs praised the Renwick’s move “to go full on with the interactivity” in line with Burning Man’s participatory ethos.

Translating works from a festival in the expansive, inhospitable desert to a museum setting also offered artists the chance to “create a totally immersive environment” she said, as shadows generated from her geometric sculptures danced on the gallery walls.

Intriciate laser cutouts in the “HYBYCOZO” installation by Yelena Filipchuk and Serge Beaulieu create dancing shadows on gallery walls

For Filipchuk, the show underscores Burning Man’s status as a cultural petri dish but also as an “American institution.”

“It really represents American values, like creativity, freedom, innovation,” she said.

Acclaimed artist Leo Villareal, whose mirrored light installation glitters above the museum’s staircase, sees the normally ephemeral Burning Man’s entrance into the museum world as part of a “major worldwide cultural movement that has taken on a life of its own.”

“I think people are responding in a huge way,” said Villareal, who is working on a large-scale piece in London to light up more than a dozen bridges over the Thames River.

“For the Smithsonian to get behind the ideas of Burning Man and put it in a show like ‘No Spectators’ is truly remarkable.”

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.