Putting on a play imagining the behind-the-scenes life of an ageing Mary (yes, that Mary, the mother of Jesus) is a controversial business.

But using that controversy as a primary means of marketing the piece is problematic business artists might be drawn to such a buzz, but the same is not necessarily true for audiences.

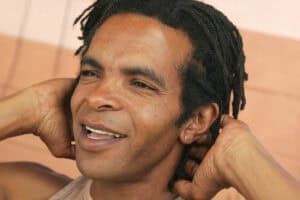

“You need to forget about religion; this is a story about a woman trying to save her son,” says Patricia Boyer, who plays the title role in a new production of The Testament Of Mary, the one-woman play based on Colm Toibin’s Man Booker Prize-nominated novel of the same name.

“She’s alone. Joseph has died. And she’s worrying, retrospectively, about what she could have done to stop Jesus getting crucified; about whether she was a good mother.

“Historically, there was a great restlessness in the Middle East in Mary’s time. Young men wanted to fight against the Roman oppression, and Jesus was doing so, gathering around him a group of men who Mary calls ‘misfits’.

“Imagine that sort of situation today: your activist son has a bunch of friends around, and you think they’re no good for him. But Mary goes into the kitchen to do chores so she doesn’t have to listen to them going on about their cause – and she regrets it later, as knowing more might have allowed her to help Jesus.

“She only hears about what he’s involved in later, and she tries to stop him, because she doesn’t want him to get hurt. She doesn’t succeed, and now, years later, she’s carrying this awful guilt.”

Scripture references to Mary only highlight a few moments in her life the Annuciation; finding the young Jesus preaching in the synagogue; the wedding in Cana; watching at the crucifixion and one or two others. Filling in the gaps as Toibin has done is speculative whatever perspective the author takes.

“This cannot be approached as ‘The Greatest Story ever Told’,” cautions Boyer. “I’m just playing a woman dealing with everyday stuff as best she can. She’s had a tough life, and she’s lost her son.” So what are people protesting about, then? (The New York run of the play was picketed at one point). “It’s a fine line,” muses Boyer.

“I don’t want her to come across as dismissive of what did or didn’t happen the miracles and that sort of thing. But I have to tell a story that includes cynicism – you imagine being in Mary’s situation without alienating the audience. The script helps with moments that highlight small details. At one point, Mary says, ‘When they [the disciples] were gone, he was gentler…'”

Such intimacy can be uncomfortable to watch: this is a woman baring her soul, with few distractions for those looking on. “Technique-wise, there is no melodrama,” says Boyer.

“Mary has had to close herself off. If she didn’t, she would have gone insane. The audience is brought in slowly. It’s like one of those interviews with a concentration camp survivor, where they’re discussing horrific details in a normal, chatty way.

“As Mary, I speak directly to the audience. It’s my responsibility to take them on this journey with me.” With this play, familiarity can be a problem. Everyone will arrive with their own preconceptions. Boyer nods: “Many people will be expecting the traditional story my first role was as the baby Jesus in a nativity play!

“But all I can do is play the role, and uncover what might have been her reality, where she was seeing Jesus do things that were against the law and she knew he knew it. And by then, her own youthful activism fleeing with Joseph to Egypt and all the rest must have seemed a long way away.”

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.