Is South Africa heading for a debt crisis?

There are clear danger signs ahead.

The mounting financial burden South Africa is facing cannot be dismissed as unworthy of serious consideration, nor reduced to a simple solution, such as printing more money.

South Africa is facing a few financial hurdles, not least the mounting foreign debt and the financial demands placed on government by state-owned entities (SOEs). The painfully slow release of March financial results for SOEs is keeping us in suspense. However, the financial status of those that have been released show a horrifying picture of complete reliance on government guarantees and bailouts in order to stay in business. If these are not brought under control, South Africa could be dragged to the edge of a financial cliff.

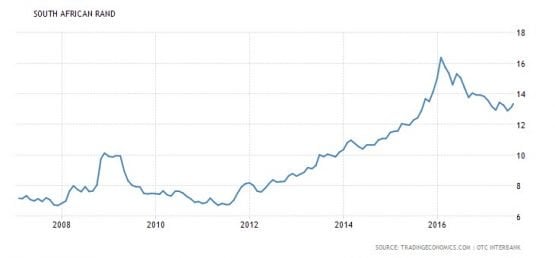

An overriding concern is the government’s US dollar-denominated gross external debt, which at June was $58.8 billion. Public corporation foreign debt, totalling $20.4 billion, should be included as it is guaranteed by government. At an exchange rate of R13.39 (at time of writing), this amounts to R1.1 trillion. Total external debt is $152.8 billion (R2 trillion). Foreign direct investment of $1.9 billion pales in comparison.

South Africa – gross external debt

.

.

.

Source: South African Reserve Bank

Servicing South Africa’s rand-denominated debt becomes more expensive with every downgrade, as higher yields will have to be paid on the bonds to compensate for the risk of default. The yield on a ten-year government bond is currently 8.5%.

The government debt-to-gross-domestic-product (GDP) ratio, an indicator of the country’s economic health, was 51.70% in 2016. In 2008 it was 27.80% of GDP. There is some debate in regard to an optimal government debt-to-GDP ratio, however, a continuing upward trajectory of this ratio would be adversely noted by the rating agencies.

‘

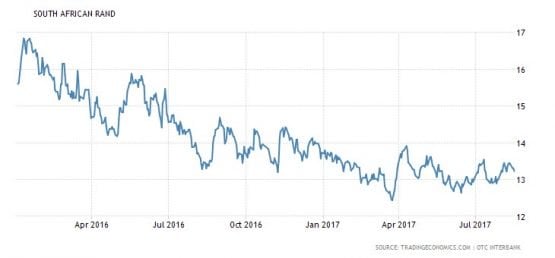

A weakening of the exchange rate will make the cost of servicing foreign debt more expensive. There are a number of external factors largely outside of South Africa’s control that impact the exchange rate, for example, quantitative easing, the growing tension between North Korea and the US, and the swings and roundabouts of the emerging markets. The internal political uncertainty, both positive and negative, adds to the roller coaster effect.

.

A one year graph shows a steadily strengthening rand, interspersed with volatile swings – a financial planner’s nightmare but a speculator’s dream.

.

The 14-point plan announced by Minister of Finance Malusi Gigaba was met with a wall of criticism, and is unlikely to do much to revive the economy. The latest figures from manufacturing and mining production are not promising, coming in less than projected, and showing a decline from the previous year. None of this augurs well for earning foreign currency.

.

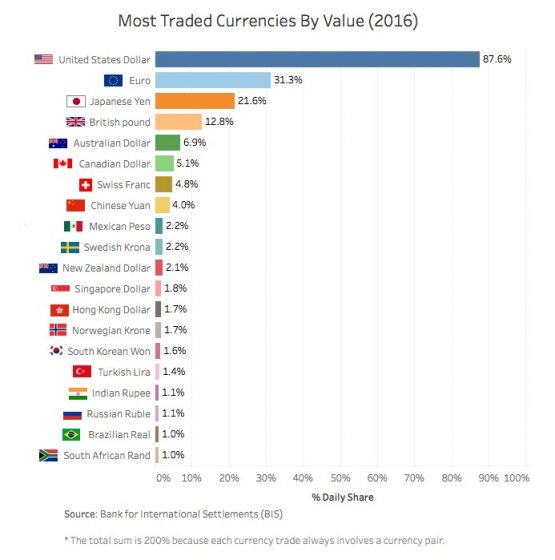

Can the debt problem be solved by printing more money? It is useful to look at the chart prepared by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) showing the most traded currencies by value in 2016. The BIS is an international financial organisation, has 60 central bank members, and represents countries that make up about 95% of world GDP. The value would be represented in dollars, but for each currency trade there is a currency pair.

.

Representing only 1% of global trade by value, it is evident that the rand does not have much clout as an international trading currency. And as South Africa is not a self-contained fully sufficient bubble, and is heavily reliant on foreign debt, printing more rand will merely devalue the currency.

South Africa is a developing economy, trying to create jobs, encourage broad-based economic empowerment, attract foreign direct investment, fund new infrastructure, stimulate growth and keep inflation in check. Almost an impossible task. It requires ongoing funding, not only to service its current debt, but to finance any future infrastructure projects.

The SOEs must urgently be placed under prudent financial management as the government can no longer afford to bail them out.

As long as funding can be sourced from abroad, South Africa will not run out of money. However, the rising cost of servicing this debt will leave little to spend internally.

There are clear danger signals ahead:

- Unemployment is currently at 27.7% and rising;

- Arresting the falling growth rate in the current economic climate is a pipe dream;

- A further downgrade will firmly sink South Africa into junk grade status, and international financial institutions will be mandated to pull out of the South African bond market;

- A depreciating rand will make foreign debt more expensive;

- The SOEs cannot service their debt, and require further funding to keep them afloat.

Urgent solutions need to be considered:

- The rating agencies will be taking a close look at SA’s growth rate, rise in debt, monetary policy and political turbulence. The rise in debt is the one factor that can be influenced. It is therefore imperative that some of the worst-performing SOEs should be auctioned off, starting with SAA, Alexkor and Denel. None of these are crucial to the economy, are debt ridden, and require further injections of cash to survive.

- Instead of desperately trying to increase taxation, there should be an evaluation of the tax incentives contained in the Income Tax Act. The cost of these incentives should be weighed against what has been achieved. The very generous tax incentive granted to toll road operators is one such incentive.

Brought to you by Moneyweb