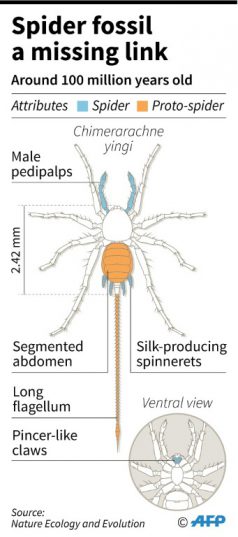

In studies published side-by-side in Nature Ecology and Evolution, one team argued that male sex organs and silk thread-producing teats link the creature to living spiders.

The other team pointed to the long tail and a segmented body to argue that Chimerarachne yingi belongs instead to a far more ancient and extinct lineage at least 380 million years old.

Either way, the researchers agree that C. yingi fills a yawning gap in the evolutionary saga of the nearly 50,000 species of spiders that spin webs and trap prey around the world today.

“It’s a missing link between the ancient Uraraneida order, which resemble spiders but have tails and no silk-making spinnerets, and modern spiders, which lack tails,” said Bo Wang, a palaeobiologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Nanjing and lead author of the study, suggesting C. yingi has more in common with their present-day, eight-legged cousins.

Remarkably, the previously unknown species was simultaneously discovered by two groups of scientists, each of which unearthed two specimens locked in translucent amber teardrops.

By coincidence, both teams submitted their findings to the same journal, which coordinated the joint release.

With a total body length of about six millimetres (one fifth of an inch) — half taken up by the tail — C. yingi is, truly, an itsy bitsy spider.

The filaments made by four nipples extruding from the back end of its abdomen were probably not there to spin webs, the researchers speculated.

– Venom glands –

Researchers agree that C. yingi fills a yawning gap in the evolutionary saga of the nearly 50,000 species of spiders around today

“Spinnerets are used to produce silk for a whole host of reasons: to wrap eggs, to make burrows, to make sleeping hammocks, or just to leave behind trails,” said Paul Selden, Wang’s co-author and a professor at the University of Kansas.

C. yingi also boasts pincer-like appendages, called pedipalps, used to transfer sperm to the female during mating, a signature trait of all living spiders.

Its whip-like tail or flagellum, also known as a telson, likely “served a sensory purpose,” Wang told AFP.

By contrast, modern spiders use silk spun into webs to monitor changes in their surroundings.

They also have venom secreted from special-purpose glands, but neither of the studies was able to confirm that C. yingi could poison its prey.

Both teams used X-ray computed tomography scanning technology to remotely dissect their specimens.

The new species was discovered in the jungles of Myanmar, which yields nearly 10 tonnes of amber every year.

“It has been coming into China where dealers have been selling to research institutions,” Wang said.

Amber has been crucial for tracing the early ancestors of spiders — but only up to a certain point.

“Spiders have soft bodies and no bones, so they don’t fossilise very well, so we rely on special conditions — especially amber — to find them,” Wang explained.

But working back in time, the trail of animal remains in amber ends about 250 million years ago, making it very difficult to trace the spider’s earliest origins.

Download our app and read this and other great stories on the move. Available for Android and iOS.