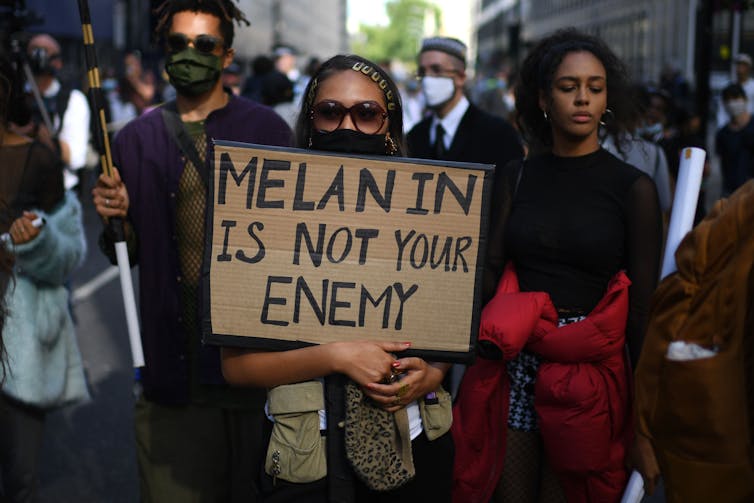

<p>Black Lives Matter activism has jolted the skin lightener industry. In June, manufacturers of skin lighteners joined other corporations in voicing support for the racial justice movement.

DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP via Getty Images

Lynn M. Thomas, University of Washington

Critics quickly pointed out the hypocrisy of voicing such support in the US while continuing to sell skin whitening products globally. Such products, they say, play off of and promote racism and colourism (which is prejudice based on preference for people with lighter skin tones) in Asia and Africa.

Manufacturers’ responses have varied. Johnson & Johnson agreed to stop selling Neutrogena Fine Fairness and Clean & Clear Fairness. Bigger players agreed to lesser changes. L’Oreal, the world’s largest cosmetics company, will remove references to “white”, “fair” and “light” from marketing its Garnier skin products.

This move acknowledges that such language promotes a narrow and anti-Black vision of beauty by presenting pale complexions as the ideal. Unilever, whose Ponds and Vaseline lines dominate sales in South Asia, will also alter the name of its top-selling brand: Fair & Lovely will soon become Glow & Lovely.

Are these meaningful changes? Will they put a dent in the global trade in skin lighteners, now estimated to reach US$24 billion by 2027?

Never before have activists and consumers in so many different countries simultaneously challenged major cosmetics manufacturers with such persistent criticism. Yet, my research on the layered history of skin lightening in the US, South Africa, and East Africa suggests that the companies’ actions are neither new nor sufficient. Ending the most dangerous dimensions of the trade – the promotion of racist beauty ideals and the use of products containing mercury and other toxic ingredients – will require ongoing consciousness-raising and effective government regulation.

Many names, many uses

Manufacturers have long used a variety of names and messages to sell skin lighteners. This variety stems partly from the competitive nature of capitalist marketing and partly from the diverse reasons why people buy these products.

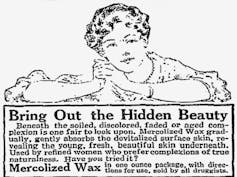

Supplied

In the early 1900s, skin lighteners were usually marketed as “freckle waxes” or “skin bleaches”. They ranked among the world’s most popular cosmetics and often contained mercury. Consumers included white, black and brown women.

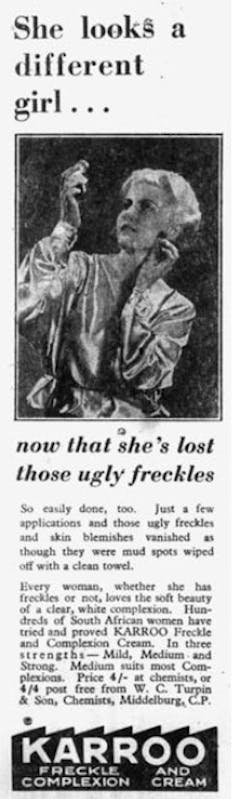

Supplied

Some women used waxes and bleaches to fade blemishes and dark spots, including freckles. Others used them to achieve an overall lighter complexion. Racialised beauty ideals – rooted in the history of slavery, colonialism, and segregation – shaped these desires.

In the 1920s and 1930s, many white consumers swapped waxes and bleaches for tanning lotions as seasonal tanning came to embody new forms of white privilege. With this shift, skin lighteners became cosmetics primarily associated with people of colour. For black and brown consumers living in places like the US, South Africa or Kenya where racism and colourism flourished, even slight differences in skin colour could carry significant political and social consequences. (Recently, some white women have returned to skin lighteners, now marketed as “anti-aging creams” and “skin brighteners”.)

During the 1950s and 1960s, manufacturers softened their marketing language. Surveys in the US found that many African American consumers took offence at the term “bleaching” – with its connotations of “whitening” – and preferred the language of lightening and toning. Hence, “skin lighteners” and “skin toners” replaced “skin bleaches”. Brands like Bleach ‘N Glow became Ultra Glow.

Unilever’s plan to swap “glow” for “fair” might be new for some Asian markets but the language of glow and brightness has been around in the US and South Africa for some time.

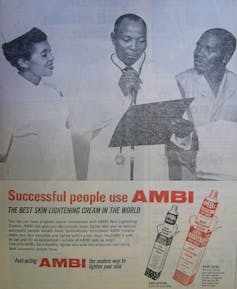

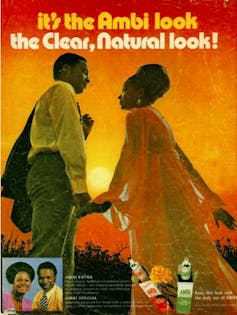

Criticism forced manufacturers to adjust in other ways. In 1971 Kenya’s postcolonial government banned Ambi skincare ads for abusing “the dignity of Africans” by claiming that “new Africans” were “light skinned Africans who used Ambi”. Black Consciousness organisers in South Africa denounced the same ads. Ambi responded by adopting a new slogan – “the clear, natural look” – and creating ads with an earthy sensibility.

Supplied

Lessons from an anti-apartheid victory

In 1991 South African activists achieved more than marketing concessions from manufacturers. What happened provides important lessons for today.

A coalition of progressive medical professionals and Black Consciousness organisers convinced the apartheid government, in its waning months, to ban all cosmetics containing depigmenting agents including harmful mercury and hydroquinone, by then the most common active ingredient. They convinced the government to become the first in the world to prohibit cosmetic advertisements from making any claims to “bleach”, “lighten” or “whiten” skin. Like today’s concessions to Black Lives Matter, South Africa’s regulations were the result of broad-based antiracist activism, the anti-apartheid movement.

Supplied

The South African efforts achieved mixed results. On the one hand, activists effectively raised awareness about the physical and psychological harm of skin lightening. This led to decreased sales during the 1980s. After the 1991 regulations were implemented, in-country manufacture shuttered and supply dried up.

But these gains did not persist. The supply of banned skin lighteners crept back as traders smuggled them in from elsewhere. Soon, domestic manufacture reemerged, this time in secret. On occasion, government officials have raided stashes of skin lighteners. Much more illegal inventory has slipped their notice. Some officials complain that they have insufficient resources to monitor all cosmetics products. Other observers blame government corruption and apathy.

Read more:

There’s a complex history of skin lighteners in Africa and beyond

Demand returned as well. During the 2000s, a new generation of users emerged, often unaware of earlier struggles against skin lighteners and the dangers they posed. In post-apartheid South Africa, as elsewhere, deeply embedded forms of racism and colourism mean that paler skin tones are often still associated with beauty and success.

Over the past decade, some African women have targeted that association. Kenyan artist Ng’endo Mukii offered a powerful critical reflection on skin lightening in her 2012 short film Yellow Fever. South Africa dermatologist Ncoza Dlova holds educational events and campaigns to teach about the dangers of skin lighteners and the beauty of natural skin colour.

Somali-American activist Amira Adawe and her organisation Beautywell does similar outreach. They pressured online retailer Amazon to stop selling products that contain mercury. Most recently, they lobbied the US Congress for $2 million in new funding for research and public education on the dangers of skin lighteners.

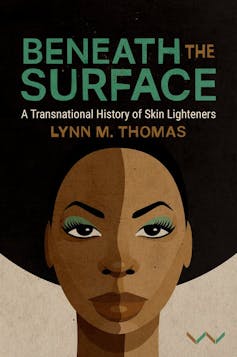

Wits University Press

L’Oreal’s and Unilever’s rebranding campaigns are inadequate. Combating the harm of skin lightening in the twenty-first century requires raising consumer awareness and challenging racist beauty ideals. It also requires that governments enforce and strengthen cosmetic regulations.

Lynn M. Thomas’s latest book Beneath the Surface: A Transnational History of Skin Lighteners is available from Wits University Press and from Duke University Press.

Lynn M. Thomas, History Professor, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.